COPYRIGHT TRIBUNAL OF AUSTRALIA

Application by Isentia Pty Limited [2021] ACopyT 2

File number: | CT 2 of 2017 CT 2 of 2018 |

The Tribunal: | GREENWOOD J (PRESIDENT) DR RHONDA SMITH (MEMBER) MS MICHELLE GROVES (MEMBER) |

Date of decision: | 15 October 2021 |

Legislation: | Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), ss 10, 14, 31, 36, 136, 154, 157, 160 |

Cases cited: | Application by Isentia Pty Limited [2020] ACopyT 2 Audio-Visual Copyright Society Ltd v New South Wales Department of School Education [1997] ACopyT 1 Copyright Agency Ltd v Department of Education of New South Wales (1985) 4 IPR 5; 59 ALR 172 Copyright Agency Ltd v New South Wales (2013) 102 IPR 85; [2013] ACopyT 1 Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Reed International Books Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 189 FCR 109 General Tire and Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre and Rubber Co Ltd [1975] 1 WLR 819 IceTV Pty Limited v Nine Network Australia Pty Limited (2009) 239 CLR 458 Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited v Copyright Tribunal of Australia (2019) 270 FCR 645 Re Applications by MCM Networking Pty Ltd (1989) 25 IPR 597 Reference by Australasian Performing Right Association Ltd [APRA]; Re Australian Broadcasting Corporation [ABC] (1985) 5 IPR 449 Reference by Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Ltd under s 154(1) of the Copyright Act 1968 (2007) 73 IPR 162; [2007] ACopyT 1 Re Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited (under s 154 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth)) (2015) 114 IPR 316; [2015] ACopyT 3 Re Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Ltd (under s 154 of Copyright Act 1968 (Cth)) (2016) 117 IPR 540; [2016] ACopyT 2 Re Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Ltd Under Section 154(1) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (2016) 125 IPR 1; [2016] ACopyT 3 Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v iiNet Ltd (2011) 194 FCR 285 Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v iiNet Limited [No 2] (2012) 248 CLR 42 University of Newcastle v Audio-Visual Society Ltd [1999] ACopyT 2 WEA Records Pty Ltd v Stereo FM Pty Ltd (1983) 1 IPR 6; 48 ALR 91 |

8 - 26 February 2021, 16, 18, 23 March 2021 | |

Category: | No Catchwords |

Number of paragraphs: | 864 |

Date of last submission/s: | 31 May 2021 |

Solicitor for the Isentia Pty Limited: | Clayton Utz |

Counsel for Meltwater Australia Pty Ltd: | Mr J Hennessy SC and Ms F St John |

Solicitor for the Meltwater Australia Pty Ltd: | Baker McKenzie |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr R Lancaster SC, Mr R Yezerski and Ms S Ross |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | MinterEllison |

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA

Copyright Act 1968

IN THE COPYRIGHT TRIBUNAL | CT 2 of 2017 | |

application by: | MELTWATER AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ABN 91 121 849 769) | |

BETWEEN: | MELTWATER AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ABN 91 121 849 769) Applicant | |

AND: | COPYRIGHT AGENCY LIMITED (ABN 53 001 228 799) Respondent | |

TRIBUNAL: | GREENWOOD J (PRESIDENT) DR RHONDA SMITH (MEMBER) MS MICHELLE GROVES (MEMBER) | |

date of order: | 15 OCTOBER 2021 | |

THE TRIBUNAL DIRECTS THAT:

1. The applicant submit to the Tribunal proposed orders giving effect to the Tribunal’s decision as set out in the Reasons for Determination generally but having particular regard to [862] and [863] of the reasons.

2. The question of the costs of the proceeding for the purposes of s 174 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) are reserved for later determination.

3. The Tribunal’s decision and reasons for determination be published from the Chambers of the President, the Hon Justice Andrew Greenwood.

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA

Copyright Act 1968

THE TRIBUNAL DIRECTS THAT:

1. The applicant submit to the Tribunal proposed orders giving effect to the Tribunal’s decision as set out in the Reasons for Determination generally but having particular regard to [862] and [863] of the reasons.

2. The question of the costs of the proceeding for the purposes of s 174 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) are reserved for later determination.

3. The Tribunal’s decision and reasons for determination be published from the Chambers of the President, the Hon Justice Andrew Greenwood.

GREENWOOD J (PRESIDENT), DR RHONDA SMITH AND MS MICHELLE GROVES:

Procedural and general contextual background

Introduction

1 These proceedings engage a broad sea of dispute between each of the applicants, Isentia Pty Limited (“Isentia”) and Meltwater Australia Pty Ltd (“Meltwater”) on the one hand, and the respondent, Copyright Australia Limited (“CA”) on the other hand, in relation to separate applications made to the Tribunal by Isentia and Meltwater under s 157(3) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (the “Act”).

2 In each application, the applicant claims, put simply for present purposes, that it requires a licence to exercise the reproduction and communication right comprised in the bundle of exclusive rights subsisting in the copyright in literary works (articles) published in print editions of newspapers and magazines (although “press clips” are now supplied digitally as PDF images of hard copy articles), or electronic online editions of newspapers and magazines (the “online” services) published by a number of well-known and some less well-known publishers. The well-known publishers include News Limited and its related entities (“News Corp” or “News Corp Australia”), Fairfax Media Limited and its related entities (“Nine Publishing” or “Nine/Fairfax”), Australian Provincial Newspapers Pty Ltd (“APN”), Rural Press Ltd (“Rural”) and West Australian Newspapers Ltd. Those publishers publish editions of their publications under prominent and some less prominent Mastheads. Some of the more prominent Mastheads, among others, are these: The Australian, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, The Financial Review, WA Today, The Daily Telegraph, The Herald Sun, Courier Mail.

3 The publishers are the owners of the copyright subsisting in the works they cause to be originated including works they then publish (putting to one side the rights they enjoy to publish the works of other (foreign) publishers under particular arrangements). That being so, they enjoy the exclusive right to reproduce each work in a material form (s 31(1)(a)(i) of the Act); to communicate the work to the public (s 31(1)(a)(iv)); and to exercise any of the other exclusive rights set out in s 31(1)(a) of the Act.

4 It almost goes without saying that the copyright in the relevant work is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, does in Australia or authorises the doing in Australia of “any act comprised in the copyright”, without the licence of the owner of the copyright: s 36(1) of the Act. The reference to the doing of an act comprised in the copyright includes the doing of that act in relation to a substantial part of the relevant work: s 14(1) of the Act. The term “communicate” means “make available online or electronically transmit (whether over a path, or a combination of paths, provided by a material substance or otherwise) a work or other subject matter …”: s 10(1) of the Act. It follows that in order for anyone to engage in an act of reproducing or communicating to the public the whole of a published article, it is necessary to obtain the licence of the publisher.

Extracts

5 Where the doing of an act in relation to a part or portion or a snippet of an article (using those terms in a non-technical and non-definitional sense for present purposes), such as a headline from an article plus a sentence or a headline and some limited number of characters is said to constitute the doing of an act comprised in the exclusive reproduction or communication right, such an act may, or may not, be properly characterised as the doing of an act in relation to a “substantial part” of the relevant work. Whether it is, or is not, an act in relation to a substantial part of the relevant work engages a question of fact and degree and consideration of the extent of the copying, the quality of that which is copied and the importance of the part copied to the work in which the copyright subsists.

6 If the relevant part, portion or snippet is not a substantial part of the relevant work, the doing of the act will not engage an act of infringement and thus the licence of the copyright owner is not required in order for the person to undertake that act, as a licence is not necessary in order to render the act a non-infringing act.

7 If the part or portion is a substantial part of the relevant work, doing the act will require the licence of the copyright owner as the act will otherwise be an infringing act.

8 It also follows, at least as a foundational matter of principle, that in order to determine whether an act of reproducing and/or communicating a part, portion or snippet of a published article engages the doing of an act in relation to a substantial part of a published article (whether a press or online article) requires an evaluative judgment to be made concerning each and every act in issue and each and every corresponding article.

9 If a person seeks to engage in acts which do involve the reproduction of a work or the communication of a work to the public (for example, the whole of an article) which thus requires the licence of the copyright owner (or, for present purposes, a licence from CA), and the licensor seeks to bring within the licence (that is, within the scope of the grant and the price and non-price terms) as a condition of the grant concerning those acts that do require a licence, other acts that do not, a question arises as to whether bringing those other acts within the licence (and particularly as a basis for the payment of charges), is “reasonable”. A further question is, can a licence in relation to acts of reproduction and communication for which a licence is necessary, also bring within the scope of the grant and the price and non-price terms, activities (acts or uses) which do not involve an act of reproduction or communication (such as value added services provided by an organisation dedicated to media analysis and media intelligence) but which might be said to be “enabled” by “access” to the copyright works of a publisher or “use” of those works in the sense that but for acts of reproduction and communication (at one level, perhaps a threshold “ingestion” level), the value added services simply could not be undertaken. If those circumstances were to be the fact, is a licence adopting such an approach one which is “reasonable” in the circumstances of the particular licensee?

10 Questions related to the principles concerning acts said to involve a “substantial part” of a work have been the subject of extensive evidence in these proceedings in the context of particular conduct and services. We will return to the specific content and context of the matter later in these reasons. For present purposes, it is sufficient to simply note, at least as a matter of principle, that when it comes to extracts of online articles, on some occasions an evaluative judgment might result in a conclusion suggesting that an act engages the notion of a substantial part of the article and on other occasions not.

11 We do not propose to try and answer in these proceedings the question of whether the acts of extracting a portion of an article whether called a “Portion” in the context of the evidence or called a “snippet” or a “teaser” or some other term such as “ingress” is or is not an exercise of the reproduction and/or communication right on the footing that the extract constitutes an act in relation to a substantial part of a corresponding article. Such a task is not possible and, in any event, impractical without looking at each article and the corresponding extract. What can be said is that, portion by portion, article by article, a relevant extract, however described, when forensically examined in the context of the article from which the extract is taken or assembled, may or may not, engage an act in relation to a substantial part of the article. We will, however, return to this topic.

12 However, it should also be noted that whatever the evaluative judgment may be, article by article, should such a task be undertaken, Isentia and Meltwater contend that there must necessarily be a qualitative difference of some substance between exercising a reproduction or communication right in relation to an entire article (that is, the whole of the article) as compared with an act engaging, for example, a headline plus the first sentence or a headline and a limited number of characters from the text of the article.

13 For present purposes, we note that CA contends that the true qualitative character of the extracts in issue in the evidence suggests an act in relation to a substantial part of the corresponding article and thus an exercise of the reproduction and communication right by acts undertaken by each applicant. CA makes a broader point about these acts to the effect that even if an extract does not engage an act in relation to a substantial part of the relevant article, there is nevertheless a “use” of the works the subject of the article which needs to be taken into account in determining the “value” of the works and the value of that use to the applicants.

Two preliminary matters

14 At this point, it is convenient to note two matters.

15 First, much of the material in evidence is either confidential or highly confidential or enjoys a particular characterisation within a hierarchy of confidentiality. In these decision reasons, the Tribunal makes reference to evidence without seeking to isolate whether the references are confidential or not. Previously in these proceedings, the Tribunal has given decision reasons which removed confidential references into a separate confidential schedule. That exercise is a time consuming one in the course of writing. Having regard to the scale of the matter and the extensive evidence put on in the proceedings, it is simply not possible to take that step in the course of writing the decision reasons. Accordingly, the decision reasons will be published to the principal solicitor for each party who enjoys access to the highest level of confidentiality under the prevailing arrangements. The principal solicitor can then determine which persons within the representative cohort for the client can properly be given access to the reasons. In due course, the decision reasons will be reviewed with a view to either redacting particular information or removing it to a confidential schedule. The decision reasons will not be published on the Tribunal’s website or the Federal Court’s website until the process just described is undertaken.

16 Second, set out below is a list of the witnesses who gave evidence in the proceedings either by affidavit or orally or both and a reference to the party who “put on” or otherwise “relied” upon the evidence of the relevant individual. The schedule below identifies the relationship between the witness and the party. Subject to later addressing a particular contention advanced by the applicants concerning the evidence given by Mr Andrew Ross which we address separately, we are satisfied that all of the witnesses who gave evidence were doing the best they could to assist the Tribunal in the resolution of the issues (and, for present purposes, by referring to Mr Ross we do not mean to convey that Mr Ross was actively seeking not to assist the Tribunal, but rather a question needs to be later addressed in relation to his evidence).

Party | Name | Role |

Isentia | Mr John Croll | Previously the Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director of Isentia Group Ltd (“Isentia Group”) (parent company of Isentia Pty Ltd (“Isentia”)) until May 2018. Currently employed as a consultant to Isentia Group. He is a shareholder in Isentia Group. |

Mr Thomas Gerstmyer | Chief Operations Officer, Isentia Group since February 2018. | |

Mr Russ Horell | Chief Commercial Officer, Isentia since November 2019. | |

Dr Christopher Pleatsikas | Expert witness: Economist and Vice President at Charles River Associates. | |

Mr Timothy Webb | Solicitor, Clayton Utz, legal representative for Isentia. | |

Meltwater | Mr Iain Boyd | Director of Accounting and Financial Controller, Meltwater, since 1 April 2020. |

Mr Holger Gafert-Stephan | Senior Director and Global GL Controller, Meltwater News International GmbH since 1 January 2021. | |

Mr Andrew Grace | Owner and director of AG Consulting Limited contracted to provide services to Meltwater. Under this arrangement, Mr Grace also holds the title within Meltwater of Global Director of Solutions Engineering (since 1 April 2018). | |

Mr David Hickey | Vice President, Sales and Marketing (Asia Pacific), Meltwater, since February 2019. | |

Mr Christian Regester | Vice President, Sales Operations and Enablement, Meltwater, globally since August 2020. | |

Mr Antony Samuel | Expert witness – accounting and valuation. Managing Director of Sapere Research Group Limited. Mr Samuel is a Forensic Accountant and Valuer. | |

Mr Andrew Stewart | Solicitor, Baker McKenzie, legal representative for Meltwater. | |

Mr Johnny Vance | Global Head of Product Marketing and Partnerships for the Meltwater Group globally since February 2019. | |

CA | Dr Jeffrey Eisenach | Expert witness: Economist, Managing Director and Co-Chair of the Communications, Media and Internet Practice at NERA Economic Consulting. |

Mr David Eisman | Director, Subscriptions and Growth, Nine Entertainment Co Pty Ltd, since January 2019 | |

Mr John Fairbairn | Solicitor, MinterEllison, legal representative for CA | |

Mr Nicholas Gray | Managing Director of the Australian, New South Wales and “Prestige Titles”, News Pty Ltd (“News Corp Australia”), since 2019 (previously the Chief Executive Officer of The Australian). | |

Mr Robert Johns | Sales and Client Services Manager, NLA Media Access Limited, which is a publisher services provider business registered in England and Wales. It is also a licensor of rights in relation to published content. | |

Mr Rodney McKemmish | Expert witness: Forensic technologist and Principal at CYTER. | |

Mr Campbell Reid | Group Executive, Corporate Affairs, Policy and Government Relations, News Corp Australia. | |

Mr Andrew Ross | Expert witness: Partner and Forensic Accountant, KordaMentha Forensic. | |

Mr Adam Suckling | Chief Executive Officer, CA, since August 2015. | |

Mr Elgar Welch | Chief Executive Officer, Streem Pty Ltd (who gave an affidavit affirmed on 28 January 2021 filed on behalf of CA). |

The publishers

17 As to the publishers that own the copyright in the particular works, some of the publishers have elected to establish a vehicle, CopyCo Pty Ltd (“CopyCo”) to represent their interests in relation to the licensing of specified works in which they (or their related entities) own the copyright. CopyCo is described by CA as a “joint venture” entity. Its current shareholders are Fairfax Digital Pty Limited, News Corp Australia, Bauer Media Pty Limited (now known as Are Media Pty Limited), Rural (or a Rural entity) and APN.

18 Various publishers have entered into agreements with CopyCo granting it a non-exclusive licence to sub-licence specified rights in certain of their publications. Those publishers include Fairfax Media Limited, News Corp, Rural, Bauer Media Pty Limited, West Australian Newspapers Ltd, Elliott Newspaper Group Pty Ltd, The Border Watch Pty Ltd and Torch Publishing Company Pty Ltd. The scope of the non-exclusive licence conferred by each publisher on CopyCo is a function of the terms of each “Publisher Agreement”. Aspects of these matters have been previously addressed by the Tribunal: Application by Isentia Pty Limited [2020] ACopyT 2 (“July 2020 Tribunal decision”).

19 Each publisher that has conferred such a non-exclusive licence on CopyCo is referred to in the proceedings as a “CopyCo Publisher”.

20 There are, of course, many publishers that have not entered into a Publisher Agreement with CopyCo. They are referred to as “non-CopyCo Publishers” and their publications are described as “non-CopyCo Publications”. They consist of a large number of smaller and independent Australian publishers including, for example, the McPherson Media Group, Star News Group and Private Media which is the publisher of Crikey and The Mandarin. They include publishers of specific publications (such as Australian Mining, Australian Photography, Fishing World, Australian Doctor, Medical Observer). The non-CopyCo Publishers and Publications also include publishers that are members of CA directly.

CA

21 As to CA, it describes itself relevantly for these proceedings, as a non-exclusive licensor of “certain reproduction and communication rights with respect to works contained in: (a) a printed edition of a newspaper, magazine or similar periodical; and (b) an electronic edition of a newspaper, website or other electronic news service (other than a journal)”. It offers “voluntary licences” on both a “blanket” and a “transactional” basis to a range of users.

22 As to CA’s relationship with CopyCo Publishers, CopyCo by an Agency Agreement dated 20 March 2000 appointed CA to act as its “agent” in granting to classes of users, including media intelligence organisations otherwise known as media monitoring organisations (“MMOs”), (such as Isentia and Meltwater), “sub-licences” (falling within the scope of the primary grant by CopyCo to CA) to exercise particular exclusive rights of CopyCo publishers.

23 CA describes its “primary role” with respect to CopyCo licensed content as one of proactively suggesting potential licences, negotiating licences within its mandate and administering those licences. Mr Suckling (for CA) describes CA’s “function” as one by which CA “develops” and “negotiates” copyright charging models and licence terms for consideration by CopyCo against the background of market conditions and a function of calculating, collecting and distributing licence fees to CopyCo.

24 As to non-CopyCo Publishers, CA says that it has been authorised by its publisher “members”, “other rights holders” (the large number of smaller and independent Australian publishers mentioned earlier), the publishers of “over 5,000 NLA titles” (including The Financial Times, the Economist and others) and the publishers of “4,000 CFC titles” (including Le Monde and Le Figaro) to grant licences to MMOs of the right to copy and communicate “over 17,000 websites, newspapers and magazines” (which includes CopyCo material).

25 CA describes its “repertoire” for licensing as spanning:

… some of the most trusted sources of quality journalism in Australia as well as more popular news sources including The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, Brisbane Times, WA Today, The Daily Telegraph, The Herald Sun, Courier Mail and news.com.au; regional titles owned by Rural Press Limited; independent editions including Crikey and The Mandarin; and [the 5,000 titles mentioned earlier including dailymail.co.uk and The Guardian, including the UK and Australian editions of each].

26 Apart from the role already described, CA is also a declared collecting society that manages certain statutory licences under the Act (such as educational and government copying licences). Although CA’s role as a statutory collecting society is not engaged by these proceedings, it seems clear enough that by reason of its role as a statutory collecting society (and thus its familiarity with the notion of “equitable remuneration”) and its role (exercised as early as 1999/2000) in negotiating and acting as a licensor of “certain reproduction and communication rights” (as earlier described), CA would necessarily be astute to the statutory concept (and the corresponding statutory constraint upon CA in proposing and negotiating licences), that a person claiming to require a licence from CA in relation to those reproduction and communication rights enjoys a right to test whether certain terms relating to the “payment of charges” or the “conditions” of such a licence put to that person are reasonable or unreasonable, in the particular circumstances.

27 The circumstance that the source of the rights the subject of the proposed licence (a sub-licence to be granted by CA as “licensor” under its grant) is one or more of a bundle of exclusive rights conferred on the publisher copyright owner (with CA standing in the shoes of the copyright owner within the limits of the grant) does not mean that CA is unconstrained, as a statutory matter, in calling for or “subjecting” a licence to terms and conditions that are, in the relevant circumstances, “unreasonable”.

The statutory provisions and aspects of the claims of the applicants

28 The source of the statutory constraint upon such a licensor in this regard is to be found in s 157 of the Act.

29 Relevantly for these proceedings, s 157(3) provides that a person “who claims” that they require a licence, and one of either s 157(3)(a) or (b) is engaged, may “apply to the Tribunal”, and if the claim is shown to be “well-founded”, the Tribunal must either make an order under either of s 157(6B)(a) or s 157(6B)(b) of the Act.

30 The “licence” contemplated by s 157(3) is a licence to be granted “by or on behalf of the owner or prospective owner of the copyright in a work … to do an act comprised in the copyright”: s 136(1) of the Act.

31 The term “licensor” is a defined term under the Act and it is common ground that CA is a licensor for the purposes of s 157(3) recognising of course that s 157(3) is not concerned with a case to which a “licence scheme” (as defined in s 136(1) of the Act) applies and nor, as mentioned, is CA engaged in its role as a statutory collecting society when engaging with Isentia and/or Meltwater or any other potential licensee of works in respect of which it has a mandate from the copyright owner.

32 As to s 157(3)(a) and (b), the first of the two alternatives (in circumstances where a person claims that they require a licence), is that a licensor has refused or failed to grant, or to procure the grant of the licence, and that in the circumstances it is unreasonable that the licence should not be granted: s 157(3)(a).

33 The second limb of s 157(3) is that a licensor proposes that the licence should be granted subject to the payment of charges, or to conditions, that are unreasonable: s 157(3)(b).

34 The case propounded by each applicant in these proceedings is that they require a licence to exercise the reproduction and communication right in literary works of the relevant publishers for the purpose of providing a “press monitoring service” and an “online monitoring service” (and, having regard to earlier licences, they required such a licence from 1 July 2018). They say that, in the case of Isentia, the licence proposed by CA to Isentia on 21 May 2018 contained terms relating to the payment of charges, and non-price conditions, that are unreasonable. That licence as so proposed, otherwise called the “CA Licence” (CA’s Further Amended Statement of Points in Answer, 15 December 2020 at [46]) was attached to an email and letter both dated 21 May 2018 from Mr Suckling (CA’s CEO) to Mr Croll (Isentia’s CEO at the relevant time).

35 Thus, Isentia contends that s 157(3)(b) is engaged. CA does not contend that the Tribunal’s jurisdiction is not properly enlivened.

36 Isentia also proposed a licence subject to the payment of charges and particular conditions. It contended that the terms and conditions as proposed were reasonable. It did so by the document annexed to its Statement of Points in Support of the Applicant’s Case dated 16 August 2019. By CA’s Statement of Points in Answer filed on 1 October 2019, CA confirmed that it would not grant a licence in the terms proposed by Isentia. Isentia claims that s 157(3)(a) is thus also engaged. Isentia has amended the terms and conditions of its proposed licence to take account of the findings set out in the July 2020 Tribunal decision. The terms of Isentia’s proposed licence are now set out in “Isentia’s Proposed Licence” annexed to Isentia’s Second Further Amended Statement of Points dated 1 December 2020: see [132]-[146] of that document. Isentia contends that the terms are reasonable.

37 It seeks an order under s 157(6B)(b) that it be granted a licence in the terms proposed by it.

38 Alternatively, it seeks an order specifying the “charges” and the “conditions” the Tribunal considers reasonable “in the circumstances in relation to Isentia”.

39 As to Meltwater, CA proposed to Meltwater on 18 May 2018, a licence in the terms of the “CA Licence” by the document described as Schedule 1 to CA’s Statement of Points in Answer as to which, see [33] of the document. Meltwater contends that the terms as to the payment of charges (which it says increases the fees payable by it by (redacted) are unreasonable and so too are the non-price conditions. Thus, s 157(3)(b) is said to be engaged. Meltwater also proposed a licence in the same terms, in effect, as the licence proposed by Isentia. That document is an annexure to Meltwater’s Further Amended Statement of Points in Support of the Applicant’s Case dated 1 December 2020; [49] and [49A]. It too says that the terms are reasonable.

40 Both Isentia and Meltwater contend that they have a well-founded claim pursuant to s 157(3)(b) because the 2018 CA Licence proposed to each of them (and which CA continues to support) contains terms as to the payment of charges and non-price conditions which are unreasonable. Alternatively, they both say that s 157(3)(a) is made good and well-founded.

41 It is convenient to now set out the text of s 157(3) and its relationship with s 157(6B) of the Act. The provisions are in these terms:

…

No licence scheme and licensor refuses or fails to grant reasonable licence

(3) A person who claims that he or she requires a licence in a case to which a licence scheme does not apply (including a case where a licence scheme has not been formulated or is not in operation) and:

(a) that a licensor has refused or failed to grant the licence, or to procure the grant of the licence, and that in the circumstances it is unreasonable that the licence should not be granted; or

(b) that a licensor proposes that the licence should be granted subject to the payment of charges, or to conditions, that are unreasonable;

may apply to the Tribunal under this section.

…

Order dealing with application under subsection (2) or (3)

(6B) If the Tribunal is satisfied that the claim of an applicant under subsection (2) or (3) is well-founded, the Tribunal must either:

(a) make an order specifying, in respect of the matters specified in the order, the charges, if any, and the conditions, that the Tribunal considers reasonable in the circumstances in relation to the applicant; or

(b) order that the applicant be granted a licence in the terms proposed by the applicant, the licensor concerned or another party to the application.

The ACCC guidelines

42 It is also convenient to note at this point s 157A of the Act in relation to the Tribunal’s obligation to have regard to guidelines issued by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (the “ACCC”) should a party to an application request the Tribunal to have regard to the guidelines. The applicants have made such a request. Section 157A is in these terms:

157A Tribunal must have regard to ACCC guidelines on request

(1) In making a decision on a reference or application under this Subdivision, the Tribunal must, if requested by a party to the reference or application, have regard to relevant guidelines (if any) made by the [ACCC].

(2) To avoid doubt, subsection (1) does not prevent the Tribunal from having regard to other relevant matters in making a decision on a reference or application under this Subdivision.

43 Later in these decision reasons, the Tribunal will address the ACCC guidelines and their relevance for the purposes of these proceedings. We propose to examine the guidelines in a little detail as we understand that this is the first proceeding before the Tribunal where parties have requested the Tribunal to take the guidelines into account.

Streem

44 Streem Pty Ltd (“Streem”) is also a media intelligence organisation or media monitoring organisation.

45 On 29 May 2018, Streem was also offered a licence by CA in terms reflecting the “CA Licence” as described by Mr Forbes (Streem’s Commercial Director) as the “CA Proposed Licence”). Mr Forbes took the view that the CA Proposed Licence contained unreasonable terms. Mr Forbes sets out his criticism of the terms of CA’s Proposed Licence at [112]-[152] of his affidavit affirmed on 26 June 2020. That affidavit was filed in support of Streem’s application to the Tribunal under s 157(3)(b). On 9 September 2019, Streem served on CA a licence on terms and conditions proposed by it together with its Statement of Points in Support of its case in the Tribunal. On 4 June 2020, Streem was given leave to file an Amended Statement of Points in Support annexing an “Amended Proposed Licence” which is substantially in the same terms as the licence proposed by Isentia. Thus, s 157(3)(a) was also said to have been engaged.

Some procedural matters

46 Procedural orders were made by the Tribunal that the Isentia, Meltwater and Streem applications under s 157(3) be heard together. It will be necessary to examine later in these decision reasons the particular history of the licence arrangements (including the interim licence arrangements) between CA and Isentia and also CA and Meltwater (and aspects of the terms of the interim arrangements between CA and Streem).

47 The hearing of the three applications which engaged extensive evidence including expert opinion evidence was set down for hearing for three weeks commencing on Monday, 12 October 2020. The proceeding as between Streem and CA settled on the preceding Friday, 9 October 2020. The settlement of the Streem proceeding had a profound effect upon the proceedings generally.

48 On the morning of the second day of the hearing on Tuesday, 13 October 2020, CA contended that the arrangements between CA and Streem gave rise to a licence agreement which represented terms and conditions agreed upon as between CA and a media monitoring entity concerning the grant of a non-exclusive licence in relation to articles published in a printed or electronic edition of a nominated newspaper, magazine or Masthead publication to undertake acts described as (redacted). We will return to the scope of the grant later in these reasons.

49 The significance of CA and Streem having agreed to enter into the licence on 9 October 2020 as just described is that CA contended before the Tribunal on 12 October 2020 that the Streem licence is “very indicative” of a directly comparable market transaction to which the Tribunal ought to have regard in deciding the questions arising in the present proceedings under ss 157(3) and (6B) of the Act. CA maintained that contention throughout the proceeding.

Aspects of the Streem licence of 9 October 2020

50 It is convenient to identify some aspects of the licence.

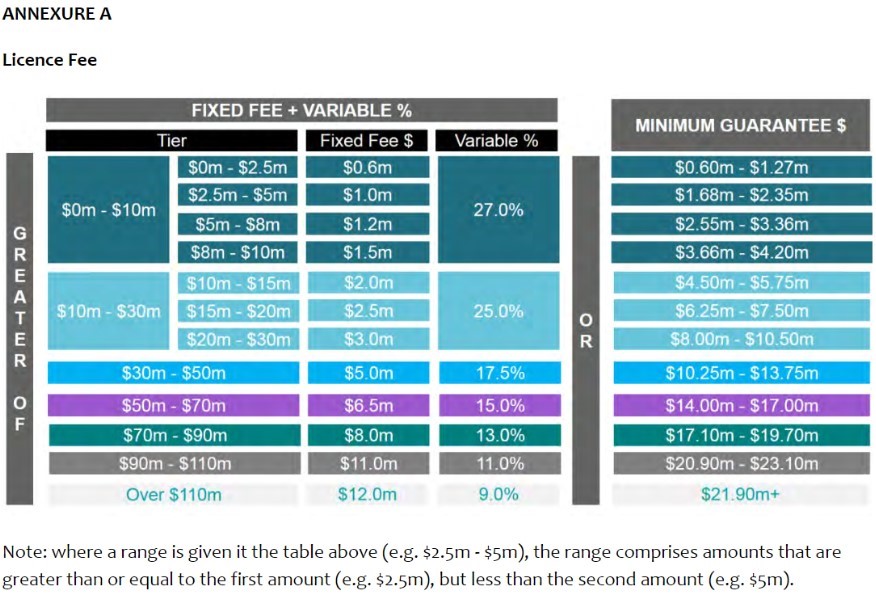

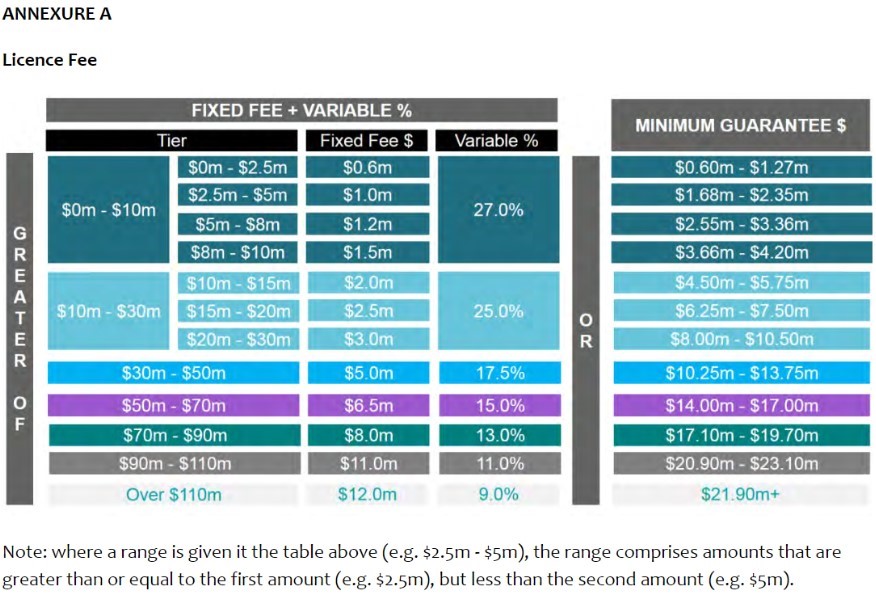

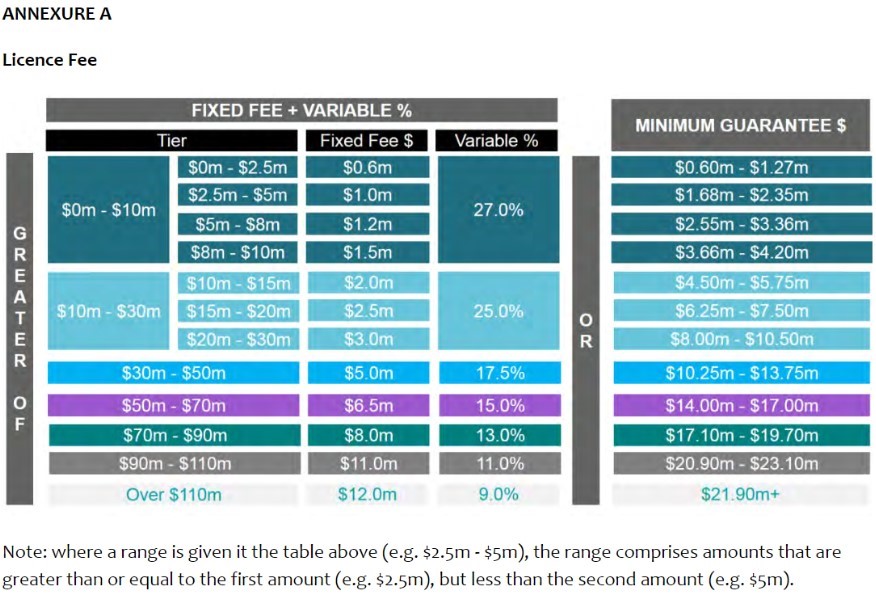

51 The Licence Agreement entered into between CA and Streem, described as a “Full Service Media Monitoring Licence” (the “FSMM Licence”), provides for the payment of a “Licence Fee” (cl 4; Schedule 1, cl 1) as specified in Schedule 2. (redacted)

52 (redacted)

53 (redacted)

54 (redacted)

55 (redacted)

56 (redacted)

57 (redacted)

58 (redacted)

59 (redacted)

60 (redacted)

61 (redacted)

62 (redacted)

63 (redacted)

64 (redacted)

65 (redacted)

66 (redacted)

67 (redacted)

Three documents related to the Streem Licence of 9 October 2020

68 As to the FSMM Licence between CA and Streem, it became clear during the course of opening submissions on 12 October and 13 October 2020 that entry into that licence needed to be understood in the context of three other documents: a Deed of Settlement of the Streem proceedings dated 9 October 2020 (the “Settlement Deed”); a Deed Poll dated 9 October 2020 given by News Corp Australia to Streem; and a Deed Poll also dated 9 October 2020 given by Nine/Fairfax to Streem.

69 (redacted)

70 (redacted)

71 (redacted)

72 (redacted)

73 The background to the licence arrangements between CA and Streem is this.

74 In July 2017, CA and Streem entered into a Press Monitoring and Online Monitoring Licence which expired on 30 June 2018. On 29 May 2018, CA offered Streem the “CA Licence” (again described in CA’s proposal as a Press Monitoring and Online Monitoring Licence). As mentioned earlier, Streem contended that terms of that licence as to the payment of charges and other conditions of that licence were unreasonable, leading to Streem’s application to the Tribunal under s 157(3) of the Act.

75 On 11 July 2018, the Tribunal made interim orders under s 160 of the Act pending the final determination of Streem’s application. The interim orders granted Streem an interim licence applying the terms of the previous agreement (which had expired on 30 June 2018) on a continuing interim basis, commencing on 1 July 2018. The interim orders contained, put simply, an adjustment mechanism such that the terms of the licence as to the payment of charges as determined by final orders of the Tribunal would also apply during the interim period from 1 July 2018 with the result that if the final terms proved to be more favourable to CA than the prevailing interim terms, Streem would pay CA an amount representing the quantum of the difference, and should the final terms prove to be more favourable to Streem than the interim charges, CA would pay Streem the difference.

76 (redacted)

77 (redacted)

78 (redacted)

79 (redacted)

80 (redacted)

81 (redacted)

82 (redacted)

83 (redacted)

The procedural consequences of CA and Streem having entered into the Streem Licence, the Deed of Settlement and the Deed Polls

84 As a result of CA’s proposition put to the Tribunal on Monday, 12 October 2020, that it would seek to rely on the FSMM Licence struck with Streem (contextualised by the Settlement Deed and the two Deed Polls all of the same date) as significant evidence of an immediately comparable transaction reflecting a market price concerning participants in the same market in relation to a licence of the same subject matter, Isentia and Meltwater contended that they would need to take instructions on many aspects of the arrangements between CA and Streem and would likely want to put on further evidence including further expert evidence. Isentia and Meltwater made those enquiries and confirmed that they would wish to put on further evidence. CA contended that it would wish to respond to that evidence.

The 11 November 2020 CA proposed licences

85 In the result, the hearing was necessarily adjourned at the request of Isentia and Meltwater without objection from CA.

86 On 11 November 2020, CA filed a document described as: Alternative licence proposed by [CA] to Applicants.

87 By that document, CA put two separate proposals to Isentia and Meltwater for the purposes of s 157(3) of the Act. The two proposals are true “alternatives” in the sense that CA maintains its contention that the terms as to the payment of charges and the non-price conditions of the CA Licence (the subject of s 157(3)(b) contentions by each applicant) are “not unreasonable”.

88 Thus, there are now three proposals put to the applicants.

89 As to the 11 November 2020 proposals, the first alternative is that a licence be granted to each applicant (which is open to acceptance by either applicant independently of the other) on the terms of a Pro Forma Licence which, (redacted) (including a “Revenue Fee” for the purposes of Schedule 2, cl 2 of 23% of “Revenue”) for a term of two years commencing on 1 October 2020. CA contended in the 11 November 2020 document that if such a licence were to be granted in respect of that period, it would resolve each application but leave unresolved questions relating to the interim period up to 1 October 2020. The Tribunal had also made interim orders in the case of Isentia and Meltwater providing for an adjustment mechanism along the lines mentioned earlier concerning the Streem Interim Licence.

90 CA’s first proposal of 11 November 2020 is described in these proceedings as the Alternative CA Licence.

91 The second alternative of 11 November 2020 proposed that a licence be granted to each applicant (again open to acceptance by either or both independently of the other) on the terms of the Pro Forma Licence (redacted) but with the Schedule 2, cl 2 Revenue Fee (redacted) from 23% to (redacted) by operation of a proposed Deed of Settlement of the relevant proceeding in each case and that the applicant enter into a proposed Pro Forma Deed of Settlement of the relevant proceeding (redacted) except that any additional payment to be made in relation to the interim licences in the period from the grant of those interim licences to 1 October 2020 is to be either agreed between the parties or determined by the Tribunal.

92 The second alternative of 11 November 2020 is described in these proceedings as the Amended Alternative CA Licence.

93 The Amended Alternative CA Licence is a proposal for the grant of a licence on terms that the relevant proceeding be settled on the terms of a proposed deed with a question held over.

94 (redacted)

95 As to “assurances of the kind given (redacted) CA recites in the 11 November 2020 document that it “enjoys no guarantee of a perpetual right to licence this content” (para 6) and “such assurances can only be offered voluntarily by the publishers”: para 7. At para 8, CA recites that having made enquiries of the Publishers, CA “understands” that if Isentia or Meltwater accepted the terms of either of the two proposals of 11 November 2020, that is, the Alternative CA Licence or the Amended Alternative CA Licence, and similar assurances were sought, then those assurances would be given by each Publisher effective from 1 October 2020 on “substantially the same terms” as the respective (redacted) “and subject to any necessary adjustments to reflect individual supply arrangements”.

96 It follows that the Amended Alternative CA Licence proposal comprises a proposal to enter into a Pro Forma Deed of Settlement of the relevant proceeding coupled with the grant of, in effect, (redacted) as contemplated by the proposed Settlement Deed (annexing the proposed Pro Forma FSMM Licence) giving effect to (redacted) in the percentage of Revenue calculation of 23% to (redacted) and taking into account CA’s “understanding” that “assurances” “similar” to those (redacted) by the third party Publishers would be given, not on the same terms, but “substantially” on the same terms “subject to any necessary adjustments to reflect individual supply arrangements”. Those assurances, as so put, would endure presumably for the two year term of the Pro Forma Licence commencing 1 October 2020.

97 CA says that each of the two alternatives are made for the purposes of, and engaged by, s 157(3) of the Act and the terms as to the payment of charges and other non-price conditions of each alternative are “not unreasonable”.

98 Isentia and Meltwater contend that, in effect, CA has abandoned the “CA Licence” proposal and now, in truth, only relies upon the Alternative CA Licence and the Amended Alternative CA Licence. Each applicant says that the Amended Alternative CA Licence is nothing more than a settlement offer rather than a licence proposal. They say that the terms of the CA Licence to the extent that that licence remains a proposal at all are unreasonable and so too are the price and non-price terms of each of the two proposals of 11 November 2020.

99 The applicants urge the Tribunal to grant a licence to each of them on the terms and conditions proposed by each of them.

100 The CA alternative licence proposals of 11 November 2020 are taken up in CA’s Further Amended Statement of Points in Answer to each application. CA says this at [55V] of that document:

… the Alternative CA Licence, the amended Alternative CA Licence, the Streem Licence and the Streem Arrangements (as defined in paragraph 1(b) of the Comparison Document) are all comparable bargains. The Streem Licence and the Streem Licence as amended by the Streem Deed [of Settlement] represent contemporaneous bargains struck between a willing buyer and a willing seller such as to render those bargains the most up to date and applicable evidence of market value available to the Tribunal.

The written submissions

101 In these proceedings, there are very many issues of fact and expert opinion in contest going to the issues raised by s 157(3) and s 157(6B). Much evidence has been filed on the various issues. The parties have filed extensive written submissions supported by schedules such as CA’s schedules: Overview of Acts comprised in Copyright by Isentia; Copyright Acts in Meltwater’s Services; Overview of the Parties Positions on Non-Price Terms in the CA Licence and the Alternative CA Licence. Meltwater relies on two schedules cross-referenced to its closing submissions. The submissions and schedules are extensive, before also taking into account the folders of closing (and opening) tender bundles handed up in support of the submissions.

102 Apart from the primary submissions, the following additional material has been put to the Tribunal:

(a) Isentia’s Reply Note and Corrections, 22 March 2021;

(b) Isentia’s Evidence References in relation to its closing submissions, 22 March 2021;

(c) Isentia’s Note in Reply to CA’s Oral Submissions, 1 April 2021;

(d) Supplementary CA Note in Reply to Isentia’s Note dated 1 April 2021 (as adopted by Meltwater on 7 April 2021), 29 April 2021;

(e) Isentia’s Note in Response to CA’s “Rejoinder Submissions” of 29 April 2021, 21 May 2021;

(f) Meltwater’s Note in Reply to CA’s Note in Reply, 31 May 2021;

(g) A joint submission by the parties in relation to aspects of the affidavit of Mr John Fairbairn dated 16 August 2021.

103 Against this background, we simply want to note one further preliminary matter. The Tribunal only asked one thing of the parties in these proceedings which was that the submissions on the many contested questions should, in effect, exhibit a degree of synthesis and reduction (to the extent possible) so as to enable the decision to be made and the decision reasons, explanatory of the decision, to be written as efficiently as possible. However, we now move on to address the many issues raised by the proceedings.

The Tribunal’s approach to determining the questions in issue

104 As to the method of deciding the questions in issue, the Tribunal has adopted the following approach. The Tribunal has considered the very extensive and detailed written submissions, heavily footnoted, supported by comprehensive oral submissions over three days from the parties. The written submissions advance the case sought to be made by each party and, point by counterpoint, extensively seek to answer each contention put against the party by its opponent.

105 We do not propose to develop a narrative of all of the detailed evidence we have heard. Rather, we propose to provide reasons for the decision we have reached on the key topics in dispute. We will, of course, address the evidence going to these topics and the relevant context. We do not propose to address in these decision reasons any evidence that has not been expressly relied upon by a party in the course of the written or oral submissions. The key topics are designed to be broad topics which capture the discussion before us and the various points of contention between the parties on so many fronts.

The key topics

106 The key broad topics which we propose to address are these:

(1) The history of the licence arrangements between CA and Isentia and CA and Meltwater.

(2) In that context, the 2016 Licence between CA and Isentia, the circumstances in which it came to be entered into, and its relevance.

(3) Aspects of the statutory question to be determined by the Tribunal under s 157 of the Act.

(4) The elements of the ACCC guidelines and their application.

(5) The activities of and services offered by Isentia and Meltwater.

(6) The question of whether the Streem FSMM Licence in the context of the arrangements between CA and Streem made on 9 October 2020 is a comparable market bargain or market rate.

(7) The extent to which Dr Eisenach’s benchmarking exercise and robustness check is of assistance to the Tribunal in deciding the questions in issue.

(8) The Alternative CA Licence and the Amended Alterative CA Licence and aspects of the evidence of Dr Pleatsikas.

(9) The licence proposals of the Isentia and Meltwater.

(10) The evidence of Mr Samuel and the critique of aspects of that evidence by Mr Ross.

(11) The non-price conditions of the licences.

107 These topics, of course, overlap but we will seek to address each topic and the resolution of the issues raised by each topic in the context of the statutory questions to be determined by the Tribunal. There is nothing rigid about these categories.

108 Before turning to each of the topics the following further important matters of fact can be conveniently noted now.

The withdrawal of titles

109 On 23 January 2020, the solicitors for CA sent a letter to the solicitors for Isentia, Meltwater and Streem, referring to interim orders made and interim licences granted by the Tribunal on 23 May 2018, 11 July 2018 and 23 April 2019 in the Meltwater, Streem and Isentia proceedings respectively, advising that News Corp had notified CA that The Australian and The Weekend Australian would no longer be publications licensed by News Corp to CopyCo. Formal notification would follow once CopyCo gave notice to CA under the provisions of the Agency Agreement.

110 On 5 February 2020, formal notice was given by CA’s solicitors to Isentia, Meltwater and Streem, that CopyCo had notified it that as from 20 March 2020 CA would cease to have the right to sub-licence The Australian and the Weekend Australia “for press clipping or webscraping”. Thus, the source of the right to copy and communicate “press clips” of those titles or “webscrape” those titles was no longer to be found in a licence (sub-licence) from CA.

111 As well, by the same letter, CA notified the three MMOs that CopyCo had notified it that CA would cease from 17 January 2021 to have the right to sub-licence the following titles of Nine/Fairfax for “press clipping or webscraping”: The Australian Financial Review, The Financial Review Smart Investor, The Financial Review BOSS, The Australian Financial Review Magazine and The Weekend Financial Review.

112 Thus, the nominated News Corp and Nine Publishing titles were withdrawn from the interim licences ordered by the Tribunal as from 20 March 2020 and 17 January 2021, respectively. (redacted) CA does not contest the proposition that these titles are important titles for a licensee seeking to provide media monitoring services. (redacted)

113 (redacted)

114 (redacted)

115 (redacted)

116 (redacted)

117 (redacted)

118 (redacted)

119 (redacted)

120 (redacted) In closing submissions, Meltwater notes that (redacted). Meltwater’s submissions also note that (redacted)

121 (redacted)

122 (redacted)

Topic (1): The history of the licence arrangements between CA and Isentia and CA and Meltwater

123 The proposals put by CA in terms of the CA Licence to Isentia on 21 May 2018 and Meltwater on 18 May 2018 did not come out of thin air. There is a history of licence arrangements between CA and each applicant which provide examples of transactions reflecting price and non-price terms in relation to related subject matter as between the licensor and licensee which illustrate agreements CA and each applicant have entered into over time. It is necessary to recognise these various methods of licensing between the same parties and, where relevant, take them into account.

CA and Isentia

124 On 27 August 2001, CA and Isentia entered into an agreement described as: Press Clipping Service Licence: Newspaper and Magazines: Copying & Communication Rights (the “2001 Isentia Licence”). (redacted). The 2001 Isentia Licence provided for a payment of a licence fee of $1.00 per article communicated to the customer. It provided for annual increases in the $1.00 rate to take account of increases in the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”). (redacted)

125 The 2001 Isentia Licence contained an acknowledgement that articles (works) of a publisher might become “Excluded Works” and thus removed from the licence.

126 In 2001, CA and Isentia also entered into an agreement described as: Press Clipping Service Licence Newspapers and Magazines Fax Transmission Licence (the “2001 Isentia Fax Licence”). That licence provided for the payment of a fee by Isentia to CA based on a revenue percentage of (redacted) of the total amount invoiced by Isentia to its customers for transmitting articles to customers by facsimile during the previous quarter. The end of the process of transmitting material by facsimile resulted in no transmission and no further payment of fees under that licence.

127 The 2016 Isentia Licence addresses not only “press monitoring” but also “online monitoring”. The notion of “scraping” or “extracting” the works of publishers from electronic editions of Mastheads and communicating a portion of such works to a customer of Isentia was the subject of a previous agreement in 2014 (the “2014 Scraping Licence”). Under that licence, CA granted Isentia a non-exclusive licence to systematically copy or extract (that is, “scrape”) works of publishers (“Licensed Works”) from electronic editions of the “Mastheads” set out in Annexure A to the licence and to communicate a portion of the scraped work to Isentia’s customer together with a link to the publisher’s website where the customer (if they elected to engage with the link) could see the entire article displayed on the publisher’s website.

128 The term of the 2014 Isentia Scraping Licence was 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015. It provided for (redacted). Notwithstanding the term, the agreement continued to operate until 30 June 2016. It too contained an “Excluded Works” provision.

129 Some clients of an MMO receiving press clippings as a result of Isentia’s upstream licence with CA would want to internally distribute and store the clippings either by email or by means of an intranet. In order to do so, the customer must also have a licence from CA to reproduce and communicate the works (solely within the customer’s organisation). These “downstream licences” were administered by Isentia on behalf of CA.

130 As mentioned, in 2016 Isentia and CA entered into a new licence for the period 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2018, the 2016 Isentia Licence. It is necessary to examine the terms of the licence and the circumstances in which it came to be concluded, for a number of reasons.

131 First, the licence represents a significant change to the charges for the grant of the licensed rights the subject of that agreement compared with the previously prevailing charges between CA and Isentia. That matter is material as an example of a licence between the parties conferring a grant of reproduction and communication rights over relevant subject matter relatively close in time to the licence CA proposed in 2018, the CA Licence. The 2016 Isentia Licence was in place for two years to 30 June 2018.

132 (redacted)

133 Third, the circumstances in which a significant change occurred to the basis for the terms as to charges to be paid by Isentia for the grant of a licence bear on the question of the extent to which the exclusive rights subsisting in the works of News Corp conferred by the Act find expression in the market positions taken by CA in the negotiations to obtain particular terms as to charges and, ultimately, the terms and conditions of the licence. Isentia and Meltwater contend that the exclusive rights conferred by the Act on News Corp (compounded, in effect, by aggregation of those rights by the publishers acting together through CA) give rise to a substantial degree of market power which was unmoderated by CA in its dealings with Isentia in relation to the 2016 Isentia Licence. Isentia and Meltwater contend that the terms as to charges and non-price terms of the proposals put by CA to each of them are unreasonable and represent the expression of the market power of News Corp which was aggregated with the market power of other CopyCo publishers.

134 Fourth, Mr Suckling and Mr Gray gave evidence about the factors leading to the position adopted by News Corp in CA’s negotiation of the 2016 Isentia Licence. In addition, Mr Suckling accepts that, put simply, the negotiations did not represent CA’s finest hour. (redacted). No attempt was made to identify a reasoned basis for the quantum of the fee demands made of Isentia which might have enable Isentia to assess the reasonableness of the proposal.

135 (redacted)

136 Before examining the 2016 Isentia Licence, aspects of the historical arrangements between CA and Meltwater ought to be noted.

CA and Meltwater

137 CA and Meltwater were parties to two licence agreements both of which expired on 30 November 2017. The first is an agreement described as: Scraping Licence. It commenced on 1 December 2014 and was amended on 7 October 2016. The second agreement is described as: Press Clipping Service Licence Newspapers and Magazines: Copying and Communication Rights (the “Press Clipping Agreement”). It was made on 12 October 2015.

138 (redacted)

139 (redacted)

140 Meltwater, in its service offerings when displaying the results of online monitoring to a customer, describes a portion of an article as an “ingress”. It represents the same thing as a portion as it consists of details of the publication in which the article appears (from which the extract is taken) and includes a limited amount of text and a link to the article.

141 (redacted)

142 (redacted)

143 (redacted)

144 (redacted)

145 (redacted)

146 (redacted)

147 The two licences expired on 30 November 2017. On 23 May 2018, the Tribunal made interim orders granting Meltwater a licence pending the determination of the proceeding on the terms of those earlier licences. (redacted)

The elements of the 2016 Isentia Licence

148 By this licence, CA grants Isentia a licence to copy and communicate Licensed Works for the purpose of providing a Press Monitoring Service and store those works for up to 12 months in a “Secure Portal”.

149 The licence authorises Isentia to make a “Scraped Copy” and to communicate a Portion to its customers (including by making that Portion available for up to 12 months in a Secure Portal) for the purpose of providing an Online Monitoring Service to its customers. This right includes the right to communicate a Portion to a customer with a link to the work on the relevant publisher’s website which will allow the customer to view the work including in circumstances where the work is behind a paywall and the customer has not separately subscribed for access.

150 By the agreement, Isentia is licensed to “create” a “searchable archive” of Licensed Works for access by Isentia’s customers of its Press Monitoring Service, and access to Portions by customers of its Online Monitoring Service, accessible in each case for up to 12 months.

151 The agreement licences Isentia to “use” the archive it has created to “display” Licensed Works or “parts” of such works to customers of its Press Monitoring Service, and to display Portions to customers of its Online Monitoring Service.

152 In order for Isentia to obtain PDF or other digital files of Licensed Works from publisher members of CopyCo, cl 3.2 makes plain that Isentia would need to “obtain appropriate access agreements with the relevant publishers”.

153 A “Licensed Work” means an Edition (as defined) and any other work which CA has been authorised to licence “other than an Excluded Work” and any work for which Isentia is licensed under another agreement (including agreements directly with publishers). A “Portion” means an extract from a single article or item published in a Licensed Work comprising any of the headline, citation and up to the greater of 50 words or 255 characters or the first sentence from the article or item. A “Scraped Copy” means a “reproduction” of a work in digital or other electronic machine-readable form obtained by “Scraping”. The term “Scraping” means the “systematic copying or extraction of electronic works by means of any automated or manual process”.

154 As to downstream licences, CA authorises Isentia to act as its agent in providing Isentia’s customers with a licence to make “downstream uses” of “Licensed Works” and “Portions” copied and communicated to them.

155 As to the Licence Fees, the total annual minimum licence fee was increased to (redacted) (excluding GST) made up of these components: a Press Monitoring Fee; an Online Monitoring Fee; and a Downstream Use Fee.

156 As to the Press Monitoring Fee (described as copying and communicating “full text print and digital print editions for [the] Press Monitoring Service”), the fees were these. For “press clips”, (redacted) multiplied by the number of clips supplied by Isentia to its customers annually (called the “variable fee clips”) if greater than the minimum number of press clips. For services described in the licence as the “subscription services” in relation to press monitoring, the fee was (redacted)

157 As to Online Monitoring (described as copying and communicating “portions from online editions for the Online Monitoring Service and downstream use by customers of content from online Editions”), a fee was payable of (redacted) (the “Minimum Fee Online”) or (redacted) of “Online Monitoring Revenue” (the “Variable Fee Online”) if greater than (redacted). The term “Online Monitoring Revenue” is defined in the licence to mean “per link revenue attributable to the Online Monitoring Service”. Recognising that the licence to scrape and communicate a Portion includes the right to communicate that Portion with a link to the work, the variable fee seems to be measured by the links communicated.

158 As to Downstream use (defined to mean “use by Isentia’s customers of content from print Editions”), the fee in relation to corporate customers was (redacted) (the “Minimum Fee Corporate Downstream”), or an amount based on the application of CA’s corporate rate card to Isentia’s customers (otherwise called the “Variable Corporate Downstream Fee”) if greater than the Minimum Fee Corporate Downstream. For government customers, the fee was (redacted) (the “Government Downstream Fee”) plus any amount received from government customers in excess (redacted) where such additional amount would not form part of the Minimum Total Annual Licence Fee: (redacted). The licence also provides that if CA licences an Isentia customer directly in respect of downstream use and the customer elects not to enter into a downstream licence with Isentia, the so-called Minimum Fee Corporate Downstream or the so-called Government Downstream Fee (whichever is applicable) is reduced by the amount of the customer’s downstream use.

159 The licence makes clear that if the sum of the components just described is greater than (redacted) the greater amount is the Licence Fee (plus the relevant excess, as just described), and if the same or less, the Licence Fee is (redacted) (plus the excess above (redacted) concerning rate card government customers, as just described).

160 (redacted)

161 The 2016 Isentia Licence is the agreement which prevailed between CA and Isentia immediately before the CA Licence proposal was put to Isentia. The circumstances in which the 2016 Isentia Licence came to be reached is a matter in controversy in these proceedings and we turn to that matter now.

Topic (2): The 2016 Isentia Licence and the circumstances in which it came to be negotiated and entered into

162 (redacted)

163 (redacted)

164 (redacted)

165 (redacted)

166 (redacted)

167 (redacted)

168 (redacted)

169 (redacted)

170 In June 2015, the former CEO of News Corp and Foxtel, Mr Kim Williams, became Chair of CA. In August, Mr Suckling was appointed CEO of CA having formerly been the Director of Policy, Corporate Affairs and Community Relations at News Corp. Mr McCaul was CA’s Director of Commercial Licensing.

171 (redacted)

172 (redacted)

173 (redacted)

174 (redacted)

175 (redacted)

176 (redacted)

177 (redacted)

178 (redacted)

179 (redacted)

180 (redacted)

181 (redacted) Isentia had other content licences including licences with: non-CopyCo publishers; broadcasters including substantially all television and radio broadcasters; licences with non-CA publisher members of print and online publications including The Guardian and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation; and content licences with social media networks.

182 (redacted)

183 (redacted)

184 (redacted)

185 (redacted)

186 (redacted)

187 (redacted)

188 (redacted)

189 (redacted)

190 (redacted)

191 (redacted)

192 (redacted)

193 (redacted)

194 (redacted)

195 (redacted)

196 (redacted)

197 (redacted)

198 (redacted)

199 Isentia again notes and emphasises Mr Suckling’s oral evidence that Mr McCaul’s response of 17 December 2015 reflected the position that CA had not itself undertaken any analysis of how that fee of approximately (redacted) for News Corp Mastheads was justified or supportable.

200 (redacted)

201 (redacted)

202 (redacted)

203 Again, Isentia notes Mr Suckling’s evidence that he did not know how the Nine/Fairfax number had been reached and nor did CA undertake any analysis of whether the figure was reasonable. (redacted)

204 (redacted). Again, Isentia notes Mr Suckling’s evidence on this topic to the effect that because he had been present at a CopyCo Board meeting with representatives of News Corp and Nine/Fairfax where discussion of the fact of increases sought from Isentia had occurred, to the best of his knowledge Nine/Fairfax knew that News Corp wanted an increase in their licence fees failing which News Corp was prepared to remove their mandate for their publications. However, Mr Suckling did not know whether Nine/Fairfax knew the quantum of the increase News Corp was seeking.

205 (redacted)

206 (redacted)

207 (redacted)

208 (redacted)

209 (redacted)

210 (redacted)

211 (redacted)

212 (redacted)

213 (redacted)

214 (redacted)

215 (redacted)

216 (redacted)

217 Isentia observes that Mr Croll’s account of the 2016 Isentia Licence negotiations was not challenged in cross-examination. Isentia also emphasises the evidence of Mr Croll as to the effect of the 2016 Isentia Licence. His oral evidence was this:

We lost a number of clients to Meltwater over the next 18 months. The price increases that we put into the market, there wasn’t that price elasticity in the market for clients to take on those increases. They hadn’t seen the value that we presented to them warranted a price increase. They looked for other providers in the marketplace at the time. And our churn increased significantly over that period of time, so we had to roll back the price increases. And it was a difficult competitive environment for us for the next period of time.

218 Isentia notes that the evidence of Mr Hickey for Meltwater was that Isentia’s 2016 licence fee was a significant price increase that caused them “irreparable harm in the market because they ended up with a [CA] agreement that was worse than ours”. (redacted) Isentia contends that while heightened competition from Meltwater and Streem and other factors played a role in these events, the circumstance that a (redacted) of Isentia’s revenue from all sources is expended on the licence with CA as a copyright cost, it would be unrealistic and thus unreasonable not to recognise the burden imposed upon Isentia by the CA licence fee and the impact it has had upon Isentia’s ability to operate a sustainable business.

Conclusions in relation to the negotiation of the 2016 Isentia Licence

219 The 2016 Isentia Licence does not assist the Tribunal in determining whether the terms as to the payment of charges contained in the CA Licence or the Alternative CA Licence or the Amended Alternative CA Licence are reasonable. The licence fee payable under the 2016 Isentia Licence to News Corp is the expression of the market power News Corp enjoyed in The Australian and The Weekend Australian to (redacted) unconstrained by rivalry and substitution possibilities. (redacted). Four other features of the chronology described above should be noted.

220 First, neither CA nor News Corp nor Nine Publishing explained the methodology it had applied to derive the number it sought, in any way that took account of any of the propositions advanced by Mr Croll.

221 Second, the negotiations with Isentia by CA on behalf of News Corp were conducted against the background of the threat by News Corp to withdraw access to the titles from the current arrangements.

222 Third, CA exercised no moderating voice of “reasonableness” in the negotiations but simply passed on the raw demands of News Corp and then Nine Publishing.

223 Fourth, CA exercised no voice of reason or reasonableness (redacted). Thus, a licence on the terms demanded by News Corp and also Nine Publishing had to be delivered.

Topic (3): Aspects of the statutory question to be determined by the Tribunal under s 157 of the Act

224 The scope of the statutory questions to be answered by the Tribunal begins and ends with the statutory text construed in the context of the Act taking into account the state of the jurisprudence aiding in the construction of the text.

225 Section 157(3) is set out earlier in these reasons at [41]. Section 157(3)(b) engages the question of whether the licence proposed by the licensor is subject to “the payment of charges” or to “conditions” that are “unreasonable”. Thus, the text is concerned with the relevant subject matter (charges and/or conditions) and whether the provisions are reasonable or unreasonable. Section 157(3)(a) is concerned with a licensor’s refusal or failure to grant the licence or to procure the grant of the licence, and that, in the circumstances, it is unreasonable that the licence should not be granted. Section 157(3)(a) (unlike s 157(3)(b)), expressly inquires whether “in the circumstances” it is unreasonable that the claimed licence should not be granted. Section 157(3)(b) is concerned with whether the particular charges or conditions (or both) are unreasonable (although the text of s 157(3)(b) does not use the phrase “in the circumstances”).

226 If the Tribunal is satisfied that the claims of the applicants under either limb of s 157(3) are “well-founded”, the Tribunal must either make an order specifying the charges and the conditions the Tribunal considers reasonable in the circumstances in relation to each of Isentia and Meltwater (s 157(6B)(a)) or order that each applicant be granted a licence in the terms proposed by, relevantly here, the applicant or the licensor: s 157(6B)(b).

227 So far as s 157(3)(b) is concerned, the Tribunal must determine whether any one or all of the three licences proposed by CA is or are subject to the payment of charges or non-price conditions that are unreasonable. The Tribunal must also consider whether CA has refused or failed to grant or to procure the grant of the licence each applicant claims it requires and whether in the circumstances it is unreasonable that the licence should not be granted.

228 We propose to consider the unreasonableness or otherwise of the impugned price and non-price provisions of each of the three CA proposed licences as we are required to do by s 157(3)(b) and also to consider whether it is unreasonable that the licence proposed by each applicant should not be granted. We propose to address the evidence going to each of those questions in the course of these decision reasons rather than sequentially. We note, however, that Isentia and Meltwater contend that they rely predominantly on s 157(3)(b) and thus we will focus on the challenge to the reasonableness of the terms as to the payment of charges and the non-price terms, but we also address the MMOs’ proposed licences in the circumstances prevailing between CA and each applicant.

229 We also note that although it was previously contended by CA that demonstrating a “well-founded” claim under limb (a) of s 157(3) confined the scope of a possible order under s 157(6B) and so too a claim made good under limb (b) confined the scope of a possible order under subsection (6B), it is now common ground that if the Tribunal is satisfied that either ground of s 157(3) is well-founded, the Tribunal may, in discharging the obligation under subsection (6B), make an order under either subparagraph (a) or (b) of subsection (6B) recognising that the Tribunal must, should the relevant state of satisfaction prevail, make an order under one of those subparagraphs.

The terms “unreasonable” and “reasonable”

230 The statutory text of s 157(3) and (6B) uses the terms “unreasonable” and “reasonable”. These terms are concepts of broad familiar use given content, however, in principle, by a number of considerations: the context in which the parties find themselves; the subject matter of the licence; the contended value attributed to rights granted by the licence; the content, burden and benefit cast upon the parties by the proposed terms as to the payment of charges and the non-price conditions; factors drawn from the history of previous dealings that may be relevant; and, no doubt, other matters, all informing an evaluative judgment of what is or is not reasonable including the proper approach to such questions reflected in the jurisprudence.

Background and role of market power

231 The applicants emphasise that the Copyright Bill (1968) for the Act was described by the then Attorney-General introducing the Bill, the Hon Nigel Bowen, as largely based on the work of the Copyright Law Review Committee (“CLRC” or “Committee”) chaired by Sir John Spicer. In the final CLRC Report, the Committee recommended that although one of the collecting societies, APRA, had proved to be a useful vehicle for both copyright owners of music and music users, it nevertheless controlled such a large amount of music that it could “fairly be described” as having “monopolistic control” over the public performance of musical works in Australia in which copyright subsisted. The Committee recognised a concern “expressed in many quarters” regarding “actual or potential abuse of this monopolistic power”. In the second reading speech for the Bill, the Attorney-General observed that in the musical field, the copyright owners had “so organised through licencing organisations” as to be “in a strong bargaining position” and “thus in a position to dictate the terms” on which music may be performed in public. The Attorney also recognised that the new Act, with the establishment of the role and jurisdiction of the Tribunal, would have an effect upon “substantial economic interests” built up under the existing law.

232 The Attorney was thus recognising that the conferral of a bundle of exclusive rights in relevant works coupled with the aggregation of the rights owners (as to music) for the exploitation of those rights could and did give rise to substantial economic interests. Aggregation was a particularly relevant matter in the case of musical works as it brought together in one place virtually all of the rights owners enjoying the rights in music capable of public performance in Australia. The critical role of aggregation was that it extinguished any possibility of supply side substitution and brought together a very wide group of rights owners who would otherwise have been rivals. As a result, a user seeking to exercise the public performance rights in preferred music could not just go to other music rights owners and obtain a licence to perform their works or a select number of musical works of particular copyright owners, should other particular copyright owners seek to extract terms thought to be unreasonable.

233 In circumstances where there is a narrow concentration of rights owners such as two critical publishers of print and online news, one or more of such entities may, without aggregation, be in a position to exercise a significant degree of market power derived from the exclusive rights they enjoy in the relevant works. If a licensee claims to require a licence to exercise rights in articles published in The Australian, no other print or online publication is a substitute because the demand is for content in articles published in that particular publication. The Parliament has conferred those exclusive rights on owners so as to provide incentives to originate works in which copyright is capable of subsisting. However, the conferral and subsistence of those rights in the context of the particular supply side and demand side dynamics of the transactions in which a person needs a licence and an owner has the capacity to impose or simply subject the licence to particular charges and conditions as a function of exclusivity, may give rise to charges and non-price conditions (adopted by the licensor, CA), which are properly characterised as the expression of market power. Such terms or conditions, so expressed, may be unreasonable.