COPYRIGHT TRIBUNAL OF AUSTRALIA

Copyright Agency Limited v State of New South Wales [2013] ACopyT 1

COPYRIGHT TRIBUNAL OF AUSTRALIA

Copyright Agency Limited v State of New South Wales [2013] ACopyT 1

CORRIGENDUM

1 In paragraph 81 insert ‘for an extended period to 31 December 2012’ after ‘$2.25 million’.

2 In paragraph 83 substitute ‘2011’ with ‘2012’.

3 In the second sentence of paragraph 116 substitute ‘uses’ with ‘ownership’ and insert ‘certain’ before ‘survey plans’.

I certify that the preceding three (3) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Corrigendum to the Reason for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Perram (Acting President) and Dr Catherine Riordan (Member). |

Associate:

Dated: 28 August 2013

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA | |

Copyright Act 1968 | |

IN THE COPYRIGHT TRIBUNAL | CT 2 of 2003 |

| Applicant | |

AND: | Respondent |

Tribunal: | MS CATHERINE RIORDAN (MEMBER) |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE TRIBUNAL ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to bring in orders to give effect to these reasons by 7 August 2013.

2. The matter be listed for directions on 14 August 2013 at 9.30 am to resolve any further issues.

Copyright Act 1968 | |

IN THE COPYRIGHT TRIBUNAL | CT 2 of 2003 |

BETWEEN: | COPYRIGHT AGENCY LIMITED Applicant

|

AND: | STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Respondent

|

tribunal: | PERRAM J (PRESIDENT (Acting)) DR CATHERINE RIORDAN (MEMBER) |

DATE: | 17 JULY 2013 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

[1] | |

2 CAL and the nature of its claim: distinction between reproduction and communication | [11] |

[30] | |

[35] | |

[41] | |

[42] | |

[43] | |

[44] | |

[54] | |

[60] | |

[62] | |

[63] | |

[66] | |

[69] | |

[76] | |

[85] | |

[89] | |

[106] | |

[109] | |

[116] |

REASONS FOR DETERMINATION

The Tribunal

1 The Registrar-General of the State of New South Wales is responsible for the administration of land titles in that State. One aspect of this function is the maintenance of a register of titles which requires the existence of a system by which parcels of land are precisely described by means of registered survey plans: see, for example, Real Property Act 1900 (NSW) (‘the RPA’), s 31B. These registered plans are of practical significance in the day-to-day conduct of conveyancing and also town planning and development control. For example, every contract for the sale of land is required by law to have attached to it a copy of the relevant registered survey plan and it is not uncommon to see such plans used as the basis for development applications. They have many other uses too. Reflecting this widespread use and significance, the Registrar-General is obliged by law to make available, for a fee, copies of registered plans to persons seeking them through the Land and Property Information division (‘the LPI’) of the Department of Finance & Services. It does this directly by providing a physical copy of the registered plan over the counter at its Queens Square offices or electronically from its online shop. It also provides them electronically to separate businesses known as information brokers who, in turn, on-supply them to their own clients.

4 It is accepted by all concerned that the survey plans which become registered upon lodgement with the LPI are original artistic works in which copyright, in principle, inheres (Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (‘the Act’) s 32) and that the owner of that copyright is either the surveyor who made the plan, or his or her employer: s 35(6). The nature of the bundle of rights comprising that copyright is set out fully in s 31 of the Act but, for present purposes, it is sufficient to observe that the copyright in a survey plan includes the right to reproduce it (s 31(1)(a)(i)) as well as the right to communicate it to the public (s 31(1)(a)(iv)). The parties largely proceeded on an assumption, which the Tribunal will make its own, that the provision of a hard copy over the counter was an act of reproduction and that the provision of an electronic version involved one or more communications.

5 There is no doubt that the LPI’s actions in so copying and communicating the plans would have been, if matters had merely rested there, the doing of an act comprised in the copyright and this would have been, in consequence, an infringement of that copyright: s 36(1) (‘…the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who…does…any act comprised in the copyright’).

6 However, under the Act, the Commonwealth and the States enjoy the privileged position of being entitled to do acts comprised in a copyright – relevantly for the purposes of this case, reproducing and/or communicating a registered survey plan – without infringing that copyright, provided the doing of the act is ‘for the services of the Commonwealth or a State’: s 183(1).

7 It was common ground in the argument before this Tribunal that the communication or reproduction of the registered survey plans carried out by the LPI was ‘for the services of … a State’ within the meaning of s 183(1) so that there was no question but that s 183(1) had been engaged. Consequently, there could be no suggestion that the actions of the LPI constituted an infringement of the copyright.

8 The privilege granted to the Commonwealth and States to do acts which would otherwise infringe a copyright is not, however, an unfettered bounty. It is instead accompanied by a régime under which, broadly speaking, the relevant polity is required to agree with the copyright owner (or the relevant collecting society – of which more later) the terms under which the polity’s use is to occur and, in the event that agreement cannot be reached, this Tribunal is given the function of resolving any dispute: s 183(5).

9 It is that function of the Tribunal which the applicant, Copyright Agency Limited (‘CAL’), now invokes. The central question which arises is the determination of the rate of remuneration that the State of New South Wales (‘the State’) should pay to the owners of the copyright in survey plans (or their representatives) for providing, for a fee, copies of registered survey plans in the various manners described above. As at the time of the hearing before the Tribunal, the LPI was charging $13.00 for a copy of a registered survey plan when sold in hard copy over the counter, $11.30 per plan when provided electronically from its online shop and $6.70 when provided electronically to information brokers. The $11.30 charge to the public from the online shop comprises the $6.70 charged to information brokers together with a service fee of $4.18 and GST thereon of $0.42.

10 We return below to the nature and function of CAL but, for present purposes it may be said that it represents the interests of registered surveyors. The debate between CAL and the State is narrow and concerns only those acts of copying and communication for which the LPI charged the fees set out in the preceding paragraph. Although there was an earlier debate about a number of other fee-free uses by the State, these had been resolved by the time that the hearing in the Tribunal concluded. The parties agreed that in those cases an appropriate rate was zero. The jurisdiction of the Tribunal is, however, circumscribed by the need for there to be disagreement (s 183(5)) and the Tribunal does not accept that it can determine rates which are agreed.

11 For the State, it was submitted that the Tribunal should fix as the appropriate rate $0.25 per plan; for CAL, that it should be $2.50 per plan (indexed to the consumer price index) or 20% of the retail price, whichever was greater. In this context, the notion of a retail price included, where an information broker was involved, the retail price charged by that broker (that is, not the $6.70 charged by the LPI to the information broker but the charge imposed by the broker on its client). Some of these retail prices were as high as $30.58 per plan in the case of the fees charged by one information broker to ‘casual users’.

12 It is necessary first to attend to some matters of detail.

2. CAL and the nature of its claim: distinction between reproduction and communication

13 Somewhat technical matters require account to be taken of the difference between the LPI’s actions in copying (or, to use the language of the Act, ‘reproducing’) registered survey plans and its actions in electronically communicating them. Unfortunately, these differences manifest themselves at the level of CAL’s rights to make claims in this Tribunal: s 183(5). It is necessary, therefore, to take a slight digression through the nature of collecting societies.

14 The Act contemplates the possibility that there will be collective agreement or, failing agreement, arbitration about the terms and rates upon which classes of copyright owners licence their copyright to classes of users: s 183(5). One of the devices utilised to this end is the notion of a collecting society, of which CAL is an example. Typically, such societies negotiate licence agreements with the users of copyright material and collect royalties on behalf of their members.

15 CAL is a not-for-profit company limited by guarantee whose members are owners of the copyright in works or otherwise control the copyright in works in Australia. It has both author and publisher members, and some members who are both authors and publishers. Its core business is the administration of the statutory licences which allow educational institutions to make copies and communications for educational purposes and the Commonwealth and States to make copies for the services of the Crown.

16 The provisions dealing with governmental use of copyright material are situated in Part VII of the Act. Part VII permits a role for collecting societies in respect of the making of copies by an entity such as a State (see ss 182B and 182C) but it does not, perhaps anomalously, provide for such a role in respect of the other rights comprised in a copyright set out in s 31. In particular, it does not provide a role for a collecting society in respect of the right to communicate a work to the public (s 31(1)(a)(iv)).

17 The structure of Part VII, therefore, gives rise to a bifurcation which has perhaps taken on a greater significance now that many transactions are conducted electronically and the boundary between reproduction and communication has become somewhat less clear than perhaps it once was. A role for collecting societies is accorded to them by the Act where what is involved is governmental copying or reproduction of a copyright work (s 182B(1)), but there is no role for them where the governmental use involves some other right comprised in the copyright, such as communication to the public. For these latter kinds of use, Part VII contemplates agreement not between the State and a collecting society but instead between a State and the actual owner of the copyright: s 179.

18 More formally, where a polity does an act comprised in a copyright pursuant to its privilege to use a copyright work without infringement for State purposes (i.e. pursuant to s 183(1)), it does so by virtue of s 183(5) which provides that ‘the terms for the doing of the act are such terms as are, whether before or after the act is done, agreed between the Commonwealth or the State and the owner of the copyright or, in default of agreement, as are fixed by the Copyright Tribunal’. This is broad enough, on its face, to encompass all the rights comprised in a copyright including both copying and communications: ss 31(1)(a)(i) and 31(1)(a)(iv). But s 183A(1) carves out from the ambit of s 183(5) the situation obtaining where what is involved is copying: ‘Subsection 183(4) and (5) do not apply in relation to a government (whenever it was made) if a company is the relevant collecting society for the purposes of this Division in relation to the copy and the company has not ceased operating as that collecting society’.

19 When government copying is involved it is, instead, s 183A(2) which comes into play:

If subsection 183(5) does not apply to government copies made in a particular period for the services of a government, the government must pay the relevant collecting society in relation to those copies (other than excluded copies) equitable remuneration worked out for that period using a method:

(a) agreed on by the collecting society and the government; or

(b) if there is no agreement—determined by the Tribunal under section 153K.

20 This has two important consequences. The first is that, insofar as the State communicates the registered survey plans to the public (rather than reproducing them), there is no direct role for CAL, for the relevant provision is s 183(5) and its focus is on the copyright owner and not the collecting society. On the other hand, where what occurs does involve the reproduction or copying of the registered survey plans, there is a role for CAL under s 183A(2). The second consequence is that the inquiry for the Tribunal under the two provisions is not precisely the same. Under s 183(5), the Tribunal is required to determine ‘the terms for the doing of the act’ whereas under s 183A(2) it is to determine ‘equitable remuneration’.

21 The difference between the claims under ss 183(5) and 183A(2) was reflected in CAL’s application to the Tribunal. Since it is not the copyright owner for any of the survey plans, it has no direct entitlement under s 183(5) to seek a determination from the Tribunal as to the ‘terms for the doing of the act’ by which the LPI communicates registered survey plans to members of the public, but it does have an entitlement under s 183A(2) to claim a determination of ‘equitable remuneration’ for the copying of such plans by the LPI.

22 To overcome this difficulty, CAL included in the membership application forms it had each of its members execute upon becoming a member, a general clause constituting it as the members ‘non-exclusive agent in all matters relating to the use of the Copyright Material within the scope of this Agreement’: cl 2.1. The result was submitted on its behalf to be that CAL could bring a claim under s 183(5) for the fixing of terms as the copyright owners agent. It was on that basis that CAL sought to fix the terms on which the LPI communicated the registered survey plans to the public: see Amended Application filed 22 October 2004, paragraph 13.

23 The State correctly submits that CAL’s application under s 183(5) (in relation to communications) cannot authorise the Tribunal to determine the terms as between the State and a copyright owner who is not also a member of CAL. Any such person has simply not brought an application upon which the Tribunal can adjudicate. On the other hand, a successful application under s 183A(2) (in relation to reproductions) will apply to all registered survey plans which have been copied (subject to some presently immaterial exceptions to be discussed below relating to plans in which the Crown owns the copyright and the position of those plans so old that the copyright has expired).

24 In its written submissions CAL submitted that there was ‘no valid question about [its] ability to distribute properly for communications of works of non-members’. Reference was made in the submission to the examination-in-chief of its chief executive officer, Mr Alexander. Mr Alexander’s affidavit evidence was that CAL had 186 surveyor members in New South Wales, which he described in his oral testimony as ‘close to 200’. He also felt that the matter was ‘slightly confusing’ because a number of the members were companies or institutions representing a number of surveyors. Mr Alexander believed that these figures did not vary substantially but that it would also be possible to attract new members if necessary.

25 If this evidence established that the members of CAL were identical with the owners of copyright in registered plans, then CAL’s submission would be made good. The Tribunal does not accept, however, that the evidence goes this far. There was evidence led by CAL from a surveyor, Mr McNamara, who had considerable experience in the various professional bodies representing surveyors. He gave evidence that there are about 190 surveying businesses in New South Wales with about 300 principals. This does not, however, establish an identity, or even an approximate identity, between the members of CAL and the copyright owners. Indeed, there was evidence from the Registrar-General (who is also the Surveyor-General) that, as at 18 March 2010, there were approximately 960 registered surveyors in New South Wales.

26 For that reason, the Tribunal does not accept that it can assume that there is an isomorphism between the members of CAL and the owners of the copyright in survey plans. The problem cannot, therefore, simply be ignored.

27 In those circumstances, it will be necessary for the outcome of CAL’s claim under s 183(5) in respect of communications to be limited in its application to registered plans in which the copyright is owned by a member of CAL. No doubt this is inconvenient, but it is the unavoidable outcome of the State’s submission that the jurisdiction of the Tribunal is so limited. As will become apparent, the inconvenience generated by the submission will most likely be borne by the State in any event.

28 For reasons developed below and subject to preceding paragraphs, the Tribunal proceeds on the basis that copying and communication should otherwise be treated on the same basis. Although the statutory inquiries under ss 183(5) (‘terms’) and 183A(2) (‘equitable remuneration’) are different, it was not submitted by either party that this should result in different outcomes in the Tribunal’s deliberations. Although textually different, the language of s 183(5) is broad enough to encompass a result including a grant of equitable remuneration. ‘I take it’ said Shepherd P of s 183(5), ‘that underlying the section is the intention that the [T]ribunal will act fairly and reasonably as between the parties and, by fixing appropriate terms, compensate the copyright owner for the copying which has been done:’ Re Application of Seven Dimensions Pty Ltd (1996) 35 IPR 1 at 18; [1996] ACopyT 1. That conclusion – grounded in common sense – is consistent, too, with the High Court’s indication that there is nothing in the text of, inter alia, s 183(5) which would suggest that polities were entitled to avoid giving ‘just terms’ within the meaning of s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution: Copyright Agency Ltd v State of New South Wales (2008) 233 CLR 279 at 301 [69]-[70]. In this case, then, it is appropriate to proceed on the basis that the terms to be fixed under s 183(5) should be terms which provide for equitable remuneration. The result of that conclusion is that the legal standard to be applied under both ss 183(5) and 183A(2) will be, at least in this case, the same. In saying that, the Tribunal does not suggest that, legally, the standards erected by the two provisions are necessarily the same; rather, the point is that in this case the Tribunal concludes that appropriate terms under s 183(5) would be terms providing for equitable remuneration.

29 There is a further consequence that should be noted. As we discuss below, it is difficult to identify any principled reason why the rate of equitable remuneration for the reproduction of registered survey plans should differ from the equitable remuneration rate for an electronic communication to a member of the public of the same.

30 This means, at least so far as this Tribunal is concerned, that there is no need for it to distinguish between those acts of the LPI which involve the copying of a single plan for provision to a member of the public in hard copy (i.e. reproduction) and those acts which involve the provision of a single plan in soft copy to a member of the public (i.e. communication). We did not apprehend that, in substance, either party advocated a different outcome. Regardless then of the correct taxonomy, the conclusion that the rates for copying and communicating should be the same means that the Tribunal does not need to distinguish between them when applied to individual plans.

31 We then turn to the role of survey plans in the register of titles.

3. Survey Plans in New South Wales

32 CAL submitted that the registered survey plans were ‘pillars supporting the Torrens systems in New South Wales’. This submission should be accepted. Although there remain old system titles in New South Wales, a very significant portion of titles in the State are what are known as Torrens titles, that is, titles operating in a system of title by registration. There are, in fact, four such kinds of title:

(a) land under the provisions of the Real Property Act 1900 (NSW) (‘RPA’);

(b) land (usually apartments) under the Strata Schemes (Freehold Development) Act 1973 (NSW) (‘the Freehold Strata Act’);

(c) land (usually apartments) under the Strata Schemes (Leasehold Development) Act 1986 (NSW) (‘the Leasehold Strata Act’); and

(d) land (usually larger multi-block apartment block developments) under the Community Land Development Act 1989 (NSW) (‘the CLDA’).

33 There is no need, for present purposes, to distinguish these separate registered titles. We will call them collectively Torrens titles, after Sir Robert Torrens who provided much of the impetus for their original introduction in South Australia on 1 July 1858: see James Hogg, Australian Torrens System (with Statutes) (William Clowes and Sons Ltd, 1905) at 762.

34 The critical features of all four systems are:

(a) the existence in each case of a register to be maintained by the Registrar-General: RPA s 31B; see also Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW) ss 195A and 195G;

(b) the obligation of the Registrar-General to keep the register in each case as a public record: RPA s 96B; see also Conveyancing Act s 199;

(c) the necessity for a lot to appear in a registered plan before a folio in the relevant register can be opened: RPA s 114;

(d) the regulation of requirements for plans to be able to be registered: RPA s 114; the Freehold Strata Act ss 8, 8A, 9; the Leasehold Strata Act ss 7, 10, 11; CLDA s 5(3), Sch 1; see also, Conveyancing Act s 195C(1); Conveyancing (General) Regulations 2008 (NSW);

(e) the registration of the plan by the affixing of the Registrar-General’s seal: Conveyancing Act s 195G(1);

(f) the requirement that plans which are to be registered be in registrable form: Conveyancing Act s 195F(1);

(g) the requirement that plans be prepared by registered surveyors: Conveyancing Act s 195C(1)(c); and

(h) the requirement that the Registrar-General provide a copy of a plan on request in return for a fee: RPA ss 96B, 115(1); Conveyancing Act s 199.

35 The net effect of these provisions is to place the preparation of survey plans by registered surveyors at the heart of the Torrens system. As Hogg commented (at 763), ‘[t]his system of showing transactions by means of separate maps or plans, in addition to the ordinary diagrams on the documents of title, is an important feature of the Torrens system’. Consequently, every lot must appear in a registered plan and a new plan will be lodged each time there is any further subdivision or some activity relating to the title.

36 The uses to which registered plans may be put are many. The Registrar-General gave evidence that approximately 50% of the registered plans provided by the LPI are used for purposes relating to conveyancing. This is no doubt related to the fact that Sch 1 of the Conveyancing (Sale of Land) Regulation 2010 (NSW), s 4 includes survey plans amongst the prescribed documents which vendors are required by s 52A(2)(a) of the Conveyancing Act to attach to every contract for the sale of land prior to it being signed. The balance of the requests are made by surveyors who, as discussed below, use them in the process of drawing up new plans.

37 It is necessary now to say something of the skill which goes into the making of a plan. Only registered surveyors may prepare survey plans which can be lodged with the LPI. Surveying is a profession. In order to become a registered surveyor it is necessary to obtain a university degree, which takes four years of undergraduate study, to undertake two years of practical training under the supervision of another registered surveyor, and then to obtain registration through the Board of Surveying and Spatial Information or complete a Professional Training Agreement. There are also continuing education obligations attaching to maintaining registration. The Tribunal accepts that registered surveyors represent a highly qualified and skilled profession.

38 For the purposes of a case stated earlier in these proceedings, the parties were able to agree the following account of how plans are created, which the Tribunal adopts:

43. Survey Plans must only include information that is relevant to the definition of boundaries, creation of title and any interests affecting that title.

44. In creating Survey Plans, surveyors must follow the legislative requirements that govern the preparation of Survey Plans. Surveyors use a standard checklist provided by LPI, which helps ensure that the plan of survey is compliant and fit for registration. The checklist is completed and signed by a surveyor who prepares a plan.

45. To create Survey Plan, a surveyor will first obtain copies of all of the relevant existing Survey Plans, for instance, those surrounding parcels, required to create an accurate Survey Plan that “fits in” with the surrounding survey marks. A surveyor may attend LPI personally and search the charting maps to identify the relevant plans and order a copy of the plans. Alternatively, and most commonly, the surveyor may as a commercial searching agent to conduct the necessary search of the charting maps at LPI and order copies of the relevant plans.

46. Once the survey information is at hand, the registered surveyor will research the plans and information obtained to determine how the original boundaries were determined and trace the surveys made on or near the subject land, as the original surveys help to determine which marks will assist in redefining the original boundaries. Once the registered surveyor has this information and has used it to create a strategy to locate the marks noted on the plans that are on public record, he or she is then ready to go to the property and commence what is colloquially known as field work.

47. The surveyor will then attend the site of the property and will locate the existing survey marks. The surveyor will measure and draw up a surveyor’s sketch plan of the site and will determine the location of the new boundary marks in accordance with the existing marks, using precedents, practices and procedures. These will, where prescribed, comply with relevant legislation. The surveyor will then mark on the ground the location of the boundaries and will place the necessary marks. These marks can include boundary marks, reference marks and permanent marks. The Surveying Regulation 2001 prescribes all of these marks.

48. The field work consists of physically locating marks defining the boundaries or improvements near the boundaries by measuring off fences, trees and other objects to assist in locating what are known as reference or permanent marks of survey. These marks are generally located by measuring a bearing and distance from a known point so that calculations can be made to compare the marks located in the field, with marks and dimensions shown on the previous Survey Plans that are on the public record. If few or no marks are found, then the field work becomes more intense as the search for evidence of the original boundaries intensifies, and requires a great deal of information to be collected to assist with the determination of the boundaries.

49. Once the comparisons are made between the marks and information, as found on undertaking the survey, and the marks as placed by the previous survey, a determination is made by the registered surveyor as to where, in his or her opinion, the boundary is and should be marked. Once the marks are placed to define the existing or new boundaries as a result of the field work, research and calculations, a Survey Plan is prepared so that when the title as are created over the new allotments or redefined boundaries, the new Certificate of Title refers to a plan showing bearings, distances, areas, north orientation and relationship to adjacent properties.

50. The surveyor will then be in a position to prepare a Survey Plan for lodgement at LPI. Such a plan is prepared on a prescribed form using line work and lettering as set out in the Schedule 5 Conveyancing (General) Regulation 2003. The plan is then handed on to the client to obtain the necessary approvals and for lodgement at LPI.

51. Surveyors are restricted in how they may present their Survey Plans. For instance, if additional information, which is not relevant to the definition or creation of the title of the relevant land, is set out in a proposed plan, or insufficient information is included to define the land accurately, the Survey Plan is requisitioned by LPI and the surveyor is required to amend the plan so that it complies with the legislative requirements before it can be registered. Approximately 40% of plans lodged are requisitioned for a variety of reasons.

52. Certain Survey Plans lodged for registration at LPI have contained information additional to that prescribed by legislation, for instance, the location of bridges, stormwater retention basins and trees. Such Survey Plans are requisitioned by LPI and the surveyor is asked to remove all of the information that is irrelevant to the boundary definition and title of the land parcel, even though a particular council or government authority (such as the Water Board) may have requested that this information be included as part of a development application approval.

53. For most Survey Plans, there is only one way of representing the division of a parcel of land. This means that if land is to be subdivided in a certain manner, the content and layout of the Survey Plan which accomplishes this division will inevitably be drafted in a prescribed way. If a surveyor repeats the work of a previous surveyor, the later surveyor should arrive at the same end result as the earlier surveyor and produce a plan that is the same in dimensions.

39 The evidence before the Tribunal included the highly prescriptive requirements that have been specified by the LPI as being prerequisite to registration. As we note later in these reasons, this matter is apt to suggest that the production of registered plans involves skill and effort not only on the part of the surveyors but also of those who conduct and maintain the register.

40 The cross-examination of the witness Mr McNamara (a registered surveyor) revealed that the actual drawing of the survey plans was performed by computer software following the inputting of the relevant data. Mr McNamara explained that ‘[t]here’s just a plan button and you push it and it works, yes. It’s not quite like that, but it’s – yes, it’s a lot simpler than it used to be. It’s like saying [sic] writing an essay and saying the word processor did it, you know’. This led the State to submit that the survey plans were not made as a result of independent creative acts. Since the State accepted that copyright inhered in the registered survey plans the Tribunal does not take this to be a submission to the contrary. Rather, the Tribunal receives this submission as a factor said to go to the question of equitable remuneration; that is, an argument that the remuneration which should be fixed should be lower because of the absence of independent creative acts.

41 The Tribunal does not accept this argument. Copyright subsists in a work when the work is original in the sense of not being copied from elsewhere. What is rewarded by the monopoly is not creativity but rather origination: as Keane CJ recently observed in Telstra Corporation Ltd v Phone Directories Company Pty Ltd (2010) 194 FCR 142 at 162-163 [58]: ‘[i]t may also be accepted that the level of intellectual effort necessary to produce an original literary work is not required to rise to the level of “creativity” or “inventiveness”. In determining whether a literary work is original, the focus of consideration is not upon creativity or novelty, but upon the origin of the work in some intellectual effort of the author’. The Tribunal concludes that, in assessing equitable remuneration, it should have regard to the intellectual effort that went into the creation of the plans but that, in assessing this, it ought not to discount the position of the surveyors simply because the work involved was not creative. To proceed otherwise would be to approach equitable remuneration on a basis inconsistent with the nature of the monopoly.

42 The Tribunal accepts that the level of skill which goes into the creation of the survey plans is considerable. Whilst it is true that the final process of drafting is completed with the aid of computer software, this does not detract from that proposition. On the other hand, the Tribunal notes that the determination of the prerequisites for registration lies with the LPI and that this is itself a significant input into the form of registered plans.

5. The Process of Registration

43 The stated case to which reference has already been made included the following account of the process of registration which the Tribunal accepts:

55. The plan lodgement and registration system has not changed substantially over time. The original and a copy of the plan, along with the certificate of title, have always been lodged in the Office of the Registrar-General, the Land Titles Office (the former name of the LPI), and now LPI, since the establishment of the Torrens System. Initially, Survey Plans were lodged over the counter. Since about 2002, plans have also been lodged electronically.

56. The Survey Plan is lodged for registration or pre-examination either over the counter at LPI Sydney or electronically with supporting documents in the format prescribed by legislation. A plan that is lodged electronically is examined in the same way as if it were lodged over-the-counter, using a print-out of the Survey Plan lodged electronically as the working copy. Fees charged for the registration of plans are referred to as “lodgement fees” and are prescribed by regulations.

57. The Survey Plan undergoes a preliminary check by the counter staff to ensure that it is signed and that the correct supporting documents have been provided, including:

(a) the original Survey Plan, complete with the necessary signatures and development approval;

(b) copies of the original Survey Plan

(c) a certificate of title;

(d) a surveyor’s checklist. A lodging party who does not produce the checklist at the time of lodgement, is told that the checklist will be requisitioned in due course;

(e) documentation relating to the creation of easements;

(f) the prescribed lodgement fee.

58. Each Survey Plan’s administrative details are recorded electronically on the Integrated Titling System (ITS) by the counter staff. This includes the surveyor’s name, number of lots, the purpose for creating the Survey Plan, the lodging party’s name and information on whether or not the plan is a survey or a complied plan. The counter staff also use ITS to record the Survey Plan as an unrecorded dealing on the computer, showing which title(s) is affected. Further, a new DP or SP number is allocated and affixed by a sticker onto the original plan and the plan copies. A packet is created under the new DP number and all of the documents are placed in the packet, together with a plan lodgement form, which is partly completed by the lodging party.

59. The original Survey Plan is suspended in a plan press, where it is kept until it is ready for a final check, charting and registration. In the meantime, a working copy of the Survey Plan, along with the checklist and certificate of title, is sent to the assembly section.

60. The plan assembler obtains the following documents:

(a) photocopies of the relevant charting maps obtained from the CRD and from the Central Mapping Authority (CMA);

(b) copies of all other Survey Plans shown in the surveyor’s panel. The surveyor’s panel is set out on the bottom right hand corner of the Survey Plan and contains the DP numbers on the plans used by the surveyor to create the new Survey Plan. This information is required under the regulations; and

(c) a Survey Control Information Management System search, which shows the relevant survey marks.

These documents are then added to the packet.

61. The plan assembler also checks the charting of the new Survey Plan to ensure the new DP number is on all of the affected titles and described as an unregistered dealing. In this way, the titling system (ITS) and the plan system (CRD) both reflect the lodgement of a new Survey Plan. That is, a notation of the new plan number indicates which parcel(s) the unregistered DP affects.

62. The plan assembler is a clerical officer who is not trained to undertake survey work. He or she will not check to see if any more plans should have been added to the surveyor’s panel. That is, they do not determine if the surveyor should have consulted more plans in the preparation of the Survey Plan.

63. Next, the plan assembler sends the packet to the plan examination supervisor for allocation to a plan examiner. The plan examiner is a skilled officer, trained in survey examination and in title matters.

64. The plan examiner reviews the Survey Plan to ensure that it complies with legislative requirements and that the boundaries are accurately defined. The examiner checks that the legal boundaries correspond with the boundaries marked on the ground, and that the new Survey Plan “fits in” with existing Survey Plans registered at LPI, to ensure that the correct boundary definitions are maintained. The examiner reviews the surveyor’s checklist and ensures that all of the necessary steps have been followed, including the proper signing of the Survey Plan, as required by the legislation. The plan examiner also checks the copies of the CRD and CMA maps included in the packet to ensure that all of the plans necessary to the drawing up of that particular Survey Plan have been referred to.

65. The plan examiner marks the working copy of the Survey Plan with colour-coded features. For example, certain types of survey marks are marked in yellow to indicate that the mark was placed in a previous plan and is being used to define the boundaries. If the plan examiner does not agree with the location of a feature on the Survey Plan in relation to a survey mark, the plan examiner may mark that survey mark in orange.

66. The plan examination process takes about 2 to 3 days, depending on the complexity of the Survey Plan. The plan examiner spends about one third of his or her time examining boundaries and survey information contained in the Survey Plan and about two thirds of his or her time considering issues relating to title and ownership relevant to the plan. Many issues may arise and may need to be dealt with by the examiner, for instance, the need to consider which easements and what restrictions on use will be carried forward into each new title. Another possible issue is the need to ensure that the person lodging the Survey Plan is the owner of the land the subject of the Survey Plan. For this to happen, it may be that a transfer or request to change the ownership of the relevant land must be examined and registered along with the Survey Plan. The Survey Plan must be checked to ensure that all of the persons required to sign it (including the owner and any mortgagees) have done so.

67. If the Survey Plan is compliant, it proceeds to registration on the Register. On and subsequent to registration:

(a) the original Survey Plan is dated and sealed and title is issued. The plan examiner registers the Survey Plan, by affixing the Registrar-General’s seal, and issues the title, by updating ITS;

(b) the electronic plan records held on the Document and Integrated Imaging Management System described below (DIIMS) are updated to reflect registration and the Survey Plan is “charted”, meaning that it is added to the LPI’s charting maps described above, along with the relevant information such as the DP or SP number and an indication of the new subdivisional lines;

(c) the registered original Survey Plan is scanned in to LPI’s database, DIIMS, from where it may be accessed by the public and government authorities;

(d) copies of the Survey Plan are sent to the relevant council and authorities (that is, water and telephone) as required by the regulations; and

(e) an electronic copy of the Survey Plan is sent to LPI Bathurst.

68. If the Survey Plan is not compliant and the plan examiner has determined exactly how the Survey Plan must be amended to be registered, the plan examiner issues requisitions to the surveyor and/or lodging party, setting out the problem areas that need to be addressed before the Survey Plan can be registered.

69. If the Survey Plan is requisitioned, the surveyor who prepared it has a duty to attend to answering the requisitions within a reasonable time frame, usually about two months. The non-payment of the surveyors bill by a client is not considered by LPI to be a good reason for a requisition not to be answered.

70. If the Survey Plan is not compliant and the plan examiner has not been able to make an exact determination on how it needs to be amended, the Survey Plan is sent to an LPI investigating surveyor, who determines what needs to be done so that the Survey Plan fits into the existing survey framework. Investigating surveyors have expertise in dealing with especially complex Survey Plans. Once it has been determined what amendments are required, requisitions are issued to the surveyor and/or lodging party setting out what needs to be addressed so that the Survey Plan is suitable for registration.

71. If the Survey Plan, after examination, is found to be correct according to the legislative requirements or the requisitions have been successfully addressed and the Survey Plan has been amended, it is registered and a new title is issued by the Registrar-General for any new lot created by the Survey Plan.

72. The registration of a new Survey Plan may sometimes be delayed until dealings such as transfers are lodged for registration or until the draft writer drafts the text of the new title to be issued upon registration of the Survey Plan.

73. The plan examiner sends the Survey Plan to a draft writer if the number of titles to be issued is greater than about two, or if the title being issued is complicated.

DOCUMENT IMAGING

74. Every time a Survey Plan, including any DP, community plan or SP, is registered at LPI, it is imaged electronically by the Image Capture Section of the Property Information Services Branch of LPI, and is entered into DIIMS, LPI's digital database of imaged plans. Images stored on DIIMS are not derived from the DCDB, but from the documents that are lodged, examined, amended and registered at the LPI in Sydney, and recorded in the ITS. The ITS, DIIMS and the plan room, where hard copies of the Survey Plans are kept, constitute a part of the register that is required to be kept by the Registrar-General under section 31B of the Real Property Act 1900 and section 195G of the Conveyancing Act 1919.

75. Electronic plan imaging commenced in November 1991. Plan images were previously captured on 35mm aperture cards, a type of microfilm. A private contractor was retained to convert the microfilm into a formatted database. This scanning process was done in the United States. In about 2001, the images were converted into Tagged Image File Format (TIFF), an international open systems standard format. This digital format cannot be further manipulated digitally. The steps undertaken to make a plan image are as follows.

76. First, as described above under Lodgement, Examination, Amendment and Registration of Survey Plans, the original documents, including plans, are lodged, examined to ensure that they comply with the relevant legislative requirements and, if compliant, they are registered at LPI in Sydney. That is, they are stamped and recorded in ITS and forwarded to the Image Capture Section for imaging into DIIMS. The hard copy plans are kept in storage. Each plan is inspected to ensure it is of a quality which will allow scanning.

77. Secondly, scanners are used to scan the plans into DIIMS. The scanners are adjusted so that each plan is effectively scanned. This is necessary because plans are prepared using different CAD software, which often produces a slightly different image. In order to allow the plans to be scanned effectively, the settings on the scanners are adjusted to take into account the different resolutions, as well as the lightness or darkness of the original document.

78. There is no manipulation of the plans in the imaging process, with two small exceptions. First, the scanning operator occasionally varies the settings on the machine to increase or decrease the contrast or lightness and darkness of the image. Secondly, the signatures appearing on a plan are sometimes photocopied and made darker so that they may then be scanned more effectively. In some cases, a copy is first made of the signatures appearing on a plan so that copy is more easily read by the scanner.

79. The Image Capture Section uses a Xerox scanner to create a bit-map image of the plan. This means that each small area of the plan is converted into digital information comprised of zeros and ones. This is not an optical character recognition process. An exact image of the whole plan is recorded in a digital format.

80. After scanning, the imaged documents are stored as individual TIFF files on magnetic hard disc drives and are archived to magnetic optical disks which are stored off-site for business continuity purposes. Software programs allow the plans to be accessed and displayed, using a unique key, being the plan number allocated by LPI staff in the lodgement process.

81. A small number of plans are also presently lodged electronically though “E-plan”. In this case, after registration the plan is forwarded to the Image Capture Section where a program checks each plan to ensure the TIFF file complies with the LPI software standard.

82. DIIMS stores all of the scanned images as a 200 dpi multi-paged TIFF Group IV format file, which can then be delivered in either paper or electronic format to LPI staff, Government agencies or members of the public.

6. Making the Registered Plans Available

44 The stated case described the process by which plans were made available thus:

Access to Scanned Images and the use of the DCDB

127. The Application Program Interface (API) is a set or programs that allows the electronic images stored on DIIMS, and other electronic products, to be accessed by users, including LPI staff, government bodies, information brokers, and members of the public. The API recognises requests received electronically from users, sorts those requests into title, image or Notice of Sale enquiries and allows the requests to be made to the appropriate database and the search results to be provided to the user.

128. Upon registration, images of registered Survey Plans are automatically made available to the relevant local council and other authorities, such as water, telephone, Rural Lands Protection, energy and valuation officers, for government administration purposes through the Internet Delivery Service (IDS). IDS is a simple operating system that identifies the location of each Survey Plan scanned into DIIMS, so that an image of it can be forwarded to the council and the authority responsible for that particular parcel of land. All new and amended Survey Plans are distributed by the IDS system.

129. LPI Sydney also makes the plan images available to LPI staff, government agencies, councils, relevant authorities, information brokers and members of the public through a number of mediums, which are outlined below. The access and copying fees charged by LPI are prescribed by the Real Property Regulation 2003 and the Conveyancing (General) Regulation 2003.

130. Most Survey Plans are accessed electronically, remotely, these days. However, it is still possible to access Survey Plans directly over-the-counter at LPI, Sydney. Members of the public order copies over-the-counter at LPI Sydney from time to time. Some survey searchers also request and obtain copies of documents, mainly plans, over-the-counter. Surveyor searchers and other members of the public may also obtain copies of Survey Plans though DIIMS whenever they request a copy of a Survey Plan over-the-counter.

131. Title searches and images can be accessed through the Lands website, operated by LPI. The Lands website can be accessed by any member of the public, who can log on and request documents, including imaged plans, by entering credit card details, having these details validated and accepting a service charge, which varies depending on the type of search being performed. The image is then sent to the user’s computer where it may be viewed, stored and printed out.

…

137. Since about late 1997, LPI has entered into licence agreements with information brokers, who are direct-access clients of LPI. Brokers may manage thousands of clients. The LPI acts as a wholesaler to the information brokers.

138. The licence agreement with the information brokers allows them to store an image, such as a plan, for a period of time. The reason for such storage is to allow the image to be sent to a client over a certain period. For instance, the customer’s printer may be broken when the search is first made. The information brokers contractually agree to delete searches, received after one day. The information brokers provide various documents to their clients, including title searches, and images of plans. They do not provide data derived from the DCDB.

139. The information brokers obtain images by accessing LPI’s electronic plan images through the API, which operates 7 days a week, 17 hours a day. The information brokers electronically communicate their requests to LPI through the API. The LPI then accesses the relevant document and sends a scanned image of that document through the fixed line to the information broker’s computer. The fixed line connections are a combination of frame relay lines and dedicated ISDN lines. Once the brokers have accessed the images through the API, they may provide the images to their clients through their own online applications or alternatively in hard copy. Surveyor search firms use brokers to obtain copies of Survey Plans for their client surveyors, who in turn require them to create new Survey Plans.

…

141. LPI Bathurst sells copies of the whole or part of the DCDB to the public. LPI supplies such copies in a number of digital formats. LPI supplies the DCDB in 17 different computer formats, on 10 different storage media, as well as email.

45 The difficulty for the Tribunal in assessing equitable remuneration has often enough been remarked upon: see, for example, the musings of Finkelstein DP in Copyright Agency Ltd v Queensland Department of Education [2002] ACopyT 1 at [14] (‘It is notorious that ascertaining equitable remuneration is a difficult task in almost all cases.’); and the stoicism of Sheppard P in Re Application by Seven Dimensions Pty Ltd (1996) 35 IPR 1 at 19; [1996] ACopyT 1 (‘I must do the best I can’); and of Lockhart P in Marine Engineering & Generator Services Pty Ltd v Queensland (1997) 38 IPR 422 at 426; [1997] ACopyT 2 (‘I must do the best I can on the basis of the material before me…’). In its deliberations on this matter, the Tribunal has considered a number of factors, including previous decisions of the Tribunal, exceptions within the Act, the difference between reproduction and communication, and the role of Crown copyright and expired copyright. The Tribunal also considered the royalties payable for use of comparable copyright works, the calculation of prices by LPI, and the economic evidence brought before it.

(i) Previous Cases Decided by the Tribunal

46 In Seven Dimensions the New South Wales Police Service purchased a video from Seven Dimensions for educating police officers about problems relating to sexual harassment. It substantially edited and shortened the video to make it more apt for police use. Only one copy was produced which was then shown to around 1,000 police officers.

47 The Tribunal approached the matter on the basis that, ordinarily, one would seek to determine the going or market rate of the use of the material. Although there was evidence of what the market rate for the material was, the Tribunal explicitly did not use those rates. Instead it asked itself what price would have been charged between the same parties in a hypothetical situation where both were at arms length (at 18-19):

What has to be done is to assume that the two parties were in an arms length bargaining situation. One has to assume they would have done business. Neither can be heard to say that they would not have done business on any terms. Nor, I think, could either say that they would only have done business for a sum which was grossly excessive or grossly inadequate.

48 The Tribunal downplayed the use of the market evidence led by Seven Dimensions because it concluded that the Police Service had not sought to exploit the video for commercial purposes (at 20):

The Police Service did not copy this video for the purpose of resale or because it made a tailor made production for a customer which itself wanted that production for commercial purposes. It made a one-off edited copy for its own purposes for purely internal training use which was shown over a period of a few months to no more than 1,000 or so police officers. There is reference in the evidence to a figure of 3000 officers but I think the better view of the evidence is that the figure should be 1000. The Police Service did not use the video for commercial purposes; it did not on sell it; it made no money from it; and its use of it was, comparatively speaking, extremely limited. The commercial rates which are referred to in the evidence and relied upon by Seven Dimensions seem to me inappropriate for such a use. I do not say that they are irrelevant and they are indeed the only guidepost I have toward making an award.

49 The ultimate conclusion of the Tribunal was that the market rate evidence led by Seven Dimensions resulted in an award of $9,600, whereas it awarded $5,000.

50 The State submitted that the Seven Dimensions decision was of little use in the present proceeding because the circumstances were very distinguishable. In particular, it was said that the Tribunal had been able to identify a real world market rate, which was not the case here. The Tribunal does not accept this submission. Although there was evidence of a real market rate, the Tribunal did not apply it. Instead, it sought to identify the rate which would be paid in a hypothetical transaction between the same parties at arms length on the assumption that the transaction would have occurred and that the rate agreed would have been neither grossly excessive nor inadequate.

51 The Tribunal applied the same approach in Marine Engineering. There the applicant had provided to the Fire Service a testing and maintenance schedule and a generator test and maintenance log. These served as useful materials for testing generators. The Fire Service then reproduced the schedule and log and distributed it to at least 240 third parties. It had not paid Marine Engineering anything for either. Having applied the approach in Seven Dimensions, Lockhart P concluded that the correct approach would be to determine a lump sum to reflect the actual work in creating the two documents linked with a royalty for the copies which were made. His Honour used Marine Engineering’s base hourly rates to determine the range of a base rate which he then adjusted upwards to reflect the likely course of negotiations. This was then used to fix the lump sum. His Honour then fixed a royalty rate of $10 per copy and did this without any reference to the commercial rates charged by Marine Engineering.

52 Again, the State submitted that this decision was distinguishable because it involved known commercial rates. But, at least at the level of setting the royalty rate, this was not so.

53 The Tribunal concludes that it is useful to approach the present matter on the basis of a hypothetical transaction between the same parties at arms length where it is assumed the transaction would have proceeded and the rate agreed would not have been excessive or inadequate. Unlike the circumstances in the Marine Engineering decision, it would not be appropriate to fix a one-off charge for the in-house cost of each plan because the surveyors have already received payment for that from those who originally commissioned the plans’ production.

54 The Tribunal accepts that any royalty awarded should not, therefore, include an element reflecting the costs of labour and/or production. Any other approach would carry with it the risk of double compensation. On the other hand, the Tribunal does accept that a royalty should be imposed.

55 The question then is how one should go about determining the rate for such a royalty. There is no doubt that it is of benefit to the public that there is an operational Torrens system and that registered plans are an integral part of that. On the other hand, there is no reason to think that the owners of the copyright should, in effect, be required to subsidise that system. Further, unlike the situation obtaining in the case of copying by educational institutions there is no risk that the imposition of a royalty in this case is likely to operate to deter persons from using registered plans. There is absent, therefore, the risk to the public that by setting the rate too high learning itself may be inhibited: Copyright Agency Limited v Queensland Department of Education and Others (2002) 54 IPR 19 at 34 [44]-[45]; [2002] ACopyT 1. The imposition of a royalty on the sale of registered plans by the State will have little or no impact on the demand for registered plans which is driven, instead, largely by the condition of the property market. So far as the expenses involved in the acquisition of land are concerned, the cost of a registered plan is small.

56 In its written submissions, the State developed an argument based upon fair dealing. In essence, it contended that many of its own internal acts of copying and/or communicating the plans were done in the course of research or study. If so, this engaged s 40(1) of the Act which provides:

A fair dealing with a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work, or with an adaptation of a literary, dramatic or musical work, for the purpose of research or study does not constitute an infringement of the copyright in the work.

57 However, by the end of the hearing, CAL and the State had agreed that these internal uses ought not to be remunerated. That being so, s 40(1) has no direct relevance to the three acts of copying and/or communicating that remain in dispute, all of which involve supply by the LPI to third parties of registered plans on payment of various fees.

58 The State also developed a variant of this argument in which it pointed to the fact that the end-users of registered plans in many cases (indeed, on the evidence of the Registrar-General, nearly half of all cases) were surveyors. Here it was submitted that the surveyors in preparing the plans were engaged in activities such as, or analogous to, research and study. It was nevertheless accepted in light of De Garis v Neville Jeffress Pidler Pty Ltd (1990) 37 FCR 99 at 105 that, even if that were so, the State could not satisfy the requirements of s 40(1) (the relevant study and/or research having to be done by the party in question rather than the end user). Nevertheless, so the argument was developed, the nature of the activities carried out by the end-users (here surveyors) could throw light on the appropriate level of any royalty.

59 A similar sentiment explains part of the reasoning in Copyright Agency Limited v Queensland Department of Education and Others (at 44 [85]), where the end-use by students of the copies for the purpose of education was thought to be relevant to the rate-fixing process. The Tribunal, therefore, does accept the possible relevance of the end uses to which the surveyors put the plans which they acquire. It is, however, of the view that those uses are everyday commercial uses and does not accept that that which surveyors are engaged in during the course of their everyday work is an activity of such benefit to the community that a discount from what might otherwise be an appropriate royalty should be adopted.

60 On the other hand, it is the case that the survey plans only obtain their status as registered plans as a result of not inconsiderable activity by the LPI involving checking, examination, requisition and, ultimately, registration by the affixation of the Registrar-General’s seal. In the Tribunal’s view, it would be to take a blinkered approach to ignore, in assessing the value of the copyright in registered plans, the significant skill and effort which goes into the maintenance of the requirements for such plans dictated and monitored by the LPI. In a sense, as we later discuss, the creation of the register and the various deposited plans associated with it is something of a collaboration between those maintaining the register and prescribing the nature of registered plans and those producing those plans in accordance with those requirements.

61 CAL accepted that the LPI used skill in operating the registration system but contended that the State was already compensated for this by the charges it levied (see above at [7]). The evidence of the Registrar-General was that the LPI operated on a fully distributed cost basis (we discuss this further below). It is true, no doubt, that the costs of conducting those processes is recovered by the LPI from the fees it charges. But this is not quite the current question. The inquiry at hand is the assessment of the equitable remuneration for the use of the copyright material. The surveyors, too, are fully remunerated for the production costs of making the plans by the fees they charge their clients. This does not mean that the copyright has no value (although it is certainly a relevant matter). The value of that copyright is also influenced by the unusual fact that much of the form of the plans is dictated by the LPI and, of course, ultimately that it is the Registrar-General’s act in affixing the seal to the plans which confers their status as registered plans. It is no answer to those observations to say that the LPI is compensated for those actions for their relevance is to the issue of authorial contribution.

(iii) Benefit to Surveyors and the LPI

62 CAL submitted that the State fully recovered its costs of making the plans available to the public through the fees it charges the public and the information brokers. On the other hand, the State submitted, on the basis of economic evidence, that any remuneration provided to the surveyors for the copyright would be competed away between them. In principle, the Tribunal accepts both of these submissions although neither throws much light on the appropriate remuneration to be set. The submissions do underscore, however, the futility of this litigation. Whatever the Tribunal awards will have little impact on the parties. Economically, it will result in an improvement in the position of the consumers of the services of surveyors (through decreased prices or improved services as the surveyors compete away the additional remuneration received) at the expense of the consumers of registered survey plans (when the remuneration paid to the surveyors is passed through to them in the form of increased fees).

63 The Australian Taxation Office will also incidentally benefit through the additional income tax payable by surveyors, as will CAL on the commission it charges for the collection of the remuneration. So viewed, this litigation appears to offer little benefit to those whose interests are said to be at stake.

(iv) Necessity of LPI Making Copies of Plans Available

64 The State then submitted that it was relevant that it was obliged to make copies of the plans available by s 31B of the RPA and ss 198 and 199 of the Conveyancing Act. The Tribunal regards this as of some relevance although that relevance is offset to an extent by the fact of its charging for the uses in question.

(v) Source of Demand for Plans Lies in Legal Obligations

65 Next the State submitted that regard was to be had to the circumstance that the demand for purchased copies of registered plans was significantly driven by the fact that, in many cases, a registered survey plan was required by law for particular transactions. One example of this, already mentioned above at [34], is the requirement that a vendor of land attach the relevant registered plan to the draft contract for the sale of land. The point the State sought to develop was that the ultimate users of the plans (at least in the instances presently of concern) were not acquiring them because of their copyright content, but because they were obliged to do so.

66 The Tribunal does not regard this as a useful consideration. The fact is that the plans are copied and sold to members of the public as well as surveyors. Whilst the Tribunal accepts that the end use to which the plans are put is relevant, it does not accept that the motives that the end users have in acquiring the plans is itself of significant relevance.

67 The State also submitted that, whilst the demand for plans, as a class, was likely to be high, the demand for any individual plan was likely to be low. The Tribunal accepts this but does not regard it as having any significant impact on the question at hand.

(vi) Reproduction or Communication of Plans

68 There was next a debate between the parties as to whether reproductions were to be treated on the same basis as communications. CAL submitted that some attention needed to be paid to the physical circumstances involved in communications. It was submitted that the distribution of an electronic form of a plan to an end-user (or information broker) was potentially analogous to the position obtaining in relation to slides. In Copyright Agency Ltd v University of Adelaide (1999) 151 FLR 142 at 161 [37]; [1999] ACopyT 1 Burchett P was concerned with the copying of artistic works on to a single page. Having concluded that such copies should be approached on a particular basis he then dealt separately with the position of artistic works copied onto slides:

However, where an artistic work is copied onto a slide, special considerations arise. I accept the submission of counsel for the applicant that a slide is a much more powerful use of an artistic work than a mere photocopy made in the ordinary way. A slide is designed for magnification and exhibition to a number of people. Accordingly, it should attract a special rate of equitable remuneration.

69 The Tribunal does not accept that the electronic communication of a plan to an end-user should be dealt with any differently to the physical copying of a plan over the counter. There are two aspects to this. The first is that the analogy with slides is inapt. The information broker’s role is as a conduit. The broker may only obtain a specified plan on request from a user and supply that plan to that user. Further, the electronic copy of the plan may only be held for the limited time of 30 days for each request (to allow any failure in delivery to be addressed). This state of affairs in no way resembles the operation of a slide. Rather, and as we have already indicated, the most sensible way to approach what occurs is on a basis which is largely analogous to the provision of a single copy. Secondly, to develop that point a little more, whilst it is true that each electronic sale of a plan involves – particularly in the case of plans supplied through information brokers – multiple acts of uploading, storage and sending, there is no reason to treat these as other than what they, in substance, are: i.e. the provision to a single user of a copy of a plan. In substance, all that is involved is the distinction in practical terms between provision of a hard copy and the provision of a soft copy.

70 The Tribunal sees no reason, in light of that conclusion, to treat the position of physical copies handed over the counter any differently to electronic copies communicated using various formats. The royalty rate in each case should be the same.

(vii) Crown Copyright and Expired Copyright

71 Both parties accepted that there were two situations in which the LPI sold registered plans which should not be subject to a right of remuneration in CAL. The first of these was where the Crown was itself the owner of the copyright in any given plan. This would be the case, for example, whenever the surveyor who created the plan had done so in the service of the Crown. The second concerned the situation where the copyright in a given plan had expired by the effluxion of time. This category would consist of two elements. In the first were those plans whose author died prior to 1 January 1955. Copyright in this class has expired because, prior to 1 January 2005, a copyright expired 50 years after the death of the author (s 33). The second element consists of those cases where a copyright had not expired on 1 January 2005. In that case the situation is affected by the US Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act 2004 (Cth) (Sch 9 item 120) which increased the duration of copyright to 70 years after the death of the author in the case of copyrights which had not expired on 1 January 2005. The consequence of that legislation is that, for those plans where copyright had not expired by January 2005, it will not expire before 1 January 2025.

72 In practice, this means that the plans in which copyright has expired is presently limited to those whose authors died prior to 1 January 1955. This will remain so until 1 January 2025 when there will be added to it that class of plans whose authors have died progressively on and after 1 January 1955.

73 As the Tribunal has already remarked, there was no dispute about these two matters between the parties, both of whom accepted in principle the non-remunerable nature of these two classes of plan.

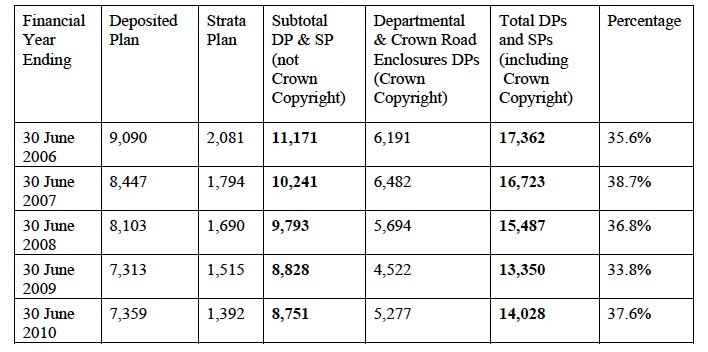

74 There was a dispute, however, about the practical question of how these plans were to be identified and how these uses were to be assessed. The Registrar-General gave evidence about two kinds of registered plan in which the Crown was the owner of the copyright: first, there were plans created within the LPI for its own purposes such as, for example, those plans arising from the bringing under the Torrens system of old systems titles; the second consisted of Crown Road enclosure plans which the Tribunal assumes arise from the titles associated with most roads. The number of such plans as a proportion of all plans in the years 30 June 2006 to 30 June 2010 were as follows:

75 This yields an average figure of 36.5%. The State did not seek to estimate the extent of plans in which there was Crown copyright beyond the two categories identified above, although it seems very likely that other such plans exist. Nor did it call for a sampling process. It did note that the above figures yielded a minimum of 36.6%.

76 Since the State has not sought to estimate the remaining Crown copyright plans (and since this is to the State’s rather than CAL’s disadvantage) the Tribunal has concluded that it should use the 36.6% figure reduced to 36.5% to reflect the five-year average. CAL submitted that a sampling procedure should be undertaken, but there is no utility in this as the process has already been done in the case of the internal LPI plans and Road Enclosure plans and yields the above figure. The averages in the table above do not appear to fluctuate markedly in any particular direction and the use of the five-year average therefore is appropriate.

77 In the case of the plans in which copyright had expired, there is no simple way for the matter to be determined. All registered plans do, however, bear the date of their registration. This is not directly useful because the issue is driven by the date upon which the author died and there is no ready connexion between the date of a plan’s registration and the date of its creator’s death. The Tribunal has concluded in that circumstance that it would be appropriate to adopt a rule of thumb. At the moment, all that one is concerned with are those plans where the surveyor died prior to 1 January 1955. The Tribunal will proceed on the basis that the plans in question were produced by the relevant surveyor 30 years before his or her death. The parties are to conduct a sampling exercise therefore to determine how many plans out of a sample of 1,000 plans were created before 1 January 1925. This proportion will then be applied as a reduction.

(viii) Previous Dealings Between the Parties

78 Both parties made submissions about the use which could be made in the Tribunal’s assessment of equitable remuneration of prior agreements reached between the parties together with the course of any negotiation between them.

79 The Tribunal accepts, in principle, the relevance of these matters. The postures of the parties in the same or similar circumstances are at least capable of throwing light on what the parties, at that time, believed. And, because the parties’ degree of knowledge about the subject matter of their negotiations is likely to be high, this in turn provides a basis for treating such material as relevant.

80 Despite the material’s potential relevance, however, the Tribunal has derived little assistance from it. The earliest agreement between CAL and the State was dated 19 September 1994 but this agreement was very narrow in scope, applying only to CAL’s members and only in relation to photocopying and facsimile. Later agreements between the parties of 1 July 2000, 23 July 2009 and 1 July 2010 were concluded on the express basis that they did not deal with survey plans.

81 As has already been mentioned, by the time of the hearing in the Tribunal, the negotiations between the parties had resulted in an agreement between them that there should be no charge where the LPI did not itself charge for the provision of plans. On the debates which remain before the Tribunal, namely those where the LPI itself charges for the provision of plans, the parties’ postures in the antecedent negotiations were not significantly different to the final positions each adopted by the end of the hearing. The LPI had suggested on 23 September 2009 that it pay a royalty of 4%. At that time, the price charged by it per plan was $6.50, so this equated to a charge of $0.26 per plan.

82 On 7 September 2012, CAL made an offer having three elements:

(a) acceptance that where the LPI provided plans for no fee there should be no charge;

(b) an offer to accept the greater of $2.50 per plan or 20% of the retail price (to be indexed) charged for the plan (including the retail price charged by a broker); and

(c) an offer to accept $2 million for all uses between 2003 and 31 December 2011.

83 At the hearing the parties agreed on (a) and, at the altered price of $2.25 million, agreed on (c). On (b), CAL’s position remained unchanged. For its part, the State was willing to accept $0.50 per plan if no account was taken of Crown or expired copyright and, if it was, $0.25 per plan. This reflected a royalty rate of around 4%; that is, its position remain largely unchanged.

84 The Tribunal concludes from this that the appropriate royalty lies somewhere between these two extremes. Since they are calculated on different cost bases it is not easy directly to compare them although one is obviously much larger than the other.

85 The State submitted that the $2.25 million figure agreed with respect to the period between 2003 to 2011 could throw light on the appropriate remuneration for the future. The State calculated that this approach led to a rate of $0.315. The Tribunal does not accept this argument for two reasons. First, as the underlying offer itself made plain, this was in respect of an offer which contained other elements of compromise. It is not necessarily to be thought that it would be sound to pluck out one part of the bargain and to treat it on a stand-alone basis. Secondly, and perhaps in development of the first point, the quality of the retrospective payment as a compromise is borne out by the disparity between it and the rates which remain in dispute between the parties.

86 For those reasons, the Tribunal concludes from the course of negotiations only that the appropriate royalty lies roughly between the two positions advocated by the parties.

(ix) Royalties for Other Types of Copyright Work

87 Both parties also pointed to other arrangements which were said to be comparable. CAL submitted its licence with respect to press-clippings was a useful comparator. It provided for $1.23 per clip for digital supply and $2.34 for supply, distribution and storage. The Tribunal considers this has some relevance if only to indicate in a very rough way the general territory. Of course, there are important differences as the State correctly pointed out. A press-clipping service is entirely voluntary. The register of titles is quite different in that regard – all must deal with it. The licence in question also permits copying and dissemination. Further, there is lacking the relationship between journalist and copier that exists between the Registrar-General (and his/her staff) and surveyors. The press-clipping service in no way dictates the form of the articles it clips nor does it superintend the articles to make sure they comply with any such requirements.